|

Editor's last word:

The structuring of electrons in the first many elements is very orderly, very patterned, easy to understand. With this introduction, one might imagine that the entire array of 118 elements – virtually by necessity, as per some embedded plan – would follow through on this readily-connect-the-dots scheme of things. Alas, we are disappointed.

After being introduced to the extremely formulaic systemization of the placement of electrons in the first many elements, I sought for explanation, from many sources, concerning how this orderly unfolding might present itself in the subsequent elements on the Periodic Table.

But I could find no easily-apprehended discourse on this subject.

This was odd, I thought. The reason for this seeming lack of forthcomingness, as I would learn, is that the electron patterning goes all to hell in the elements farther along the Table. It’s so chaotic that no one wanted to, or could, address this.

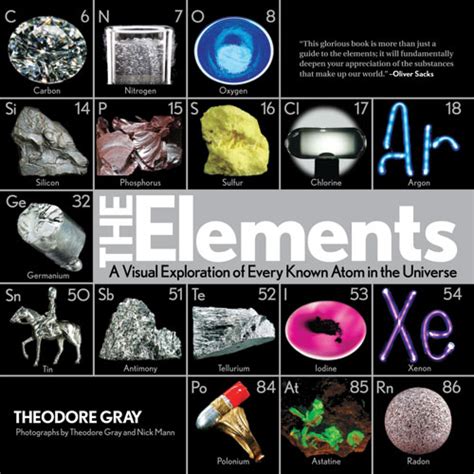

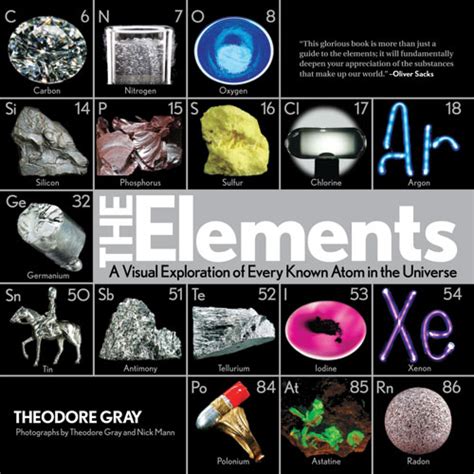

However, in the book, “The Elements” by Theodore Gray, a wonderful chart is presented, with each element, in sequential order, offering easy-to-follow graphic representation of the haphazardness of the later electron placements.

Actually, though, even this is wrong as, while there is a kind of order, it’s so off-the-wall that it’s very hard to explain. In essence, as one goes “up the line” with the later elements, after the first three shells are filled, one might see electrons filling the fifth shell, but only partially, and then ratcheting up to the seventh shell to fill a few, and then backtracking and filling the fourth. I’m giving a very generalized view here, and you will need to see Gray’s book for yourself for the actual system, but the point is, after those first several elements, with their “perfect” ordering – which reminds one of the “perfect” circular obits that early scientists imagined that the planets were “required” to have – the logical structuring suddenly all falls apart.

Or not.

My own view is that there is a patterning, but a very complicated one, not so picture-postcard easy to discern. Nature, as we learn, is always beautiful in its symmetry as it presents itself to the searcher for truth, but not in a facile and so-predictable manner.

The first elements are sort of "kindergarten-easy" in their structuring -- this is why, with the early investigations, the whole system came to be called a "periodic" table, as a repeating pattern of regularity, a "periodicity," so wonderfully revealed itself.

But then, very unexpectedly, the schematic progression changed with the later elements; at least in part, as some aspects of the element-ordering did remain sequential, just to confuse you. For example, the "one more proton" rubric for each ascending element did remain in place; this was a quick gift to those requiring a sense of "certainty."

|