|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Word Gems self-knowledge, authentic living, full humanity, continual awakening

Emerson Nature

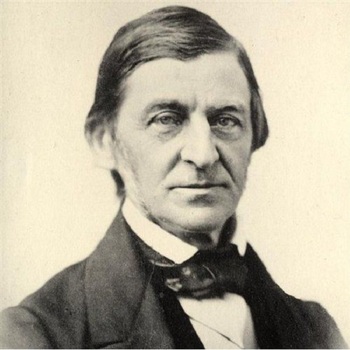

Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882)

ChatGPT offers commentary: Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Nature is in the public domain (first published 1836) and the complete text is freely available (e.g., via Project Gutenberg). Below is the full essay “Nature” by Emerson, reproduced directly from the Project Gutenberg edition (which includes the original epigraph and all chapters). I have reformatted it into numbered paragraphs Nature (1836) — Ralph Waldo EmersonEpigraph: Paraphrase: The rose, for example, speaks completely ("all"), conveying its essence and beauty to anyone who observes it carefully. Every creature is striving to grow and reach its full potential. Even something as humble as a worm participates in the grand structure of creation, gradually moving up through all levels of form and life. Glossary Modern connectionLife feels more interconnected than it first appears — small moments or choices can ripple outward and shape much bigger outcomes. We naturally search for meaning in events, sensing patterns, timing, and significance rather than pure randomness. Beauty and emotion also communicate beyond words, reaching people across differences through art, nature, and simple human gestures. At the same time, growth seems built into existence. Over time, we tend to move from more limited awareness toward greater understanding, depth, and humanity, shaped by experience and struggle. IntroductionParagraph 1: Our age is retrospective. It builds the sepulchres of the fathers. It writes biographies, histories, and criticism. The foregoing generations beheld God and nature face to face; we, through their eyes. Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs? Embosomed for a season in nature, whose floods of life stream around and through us, and invite us by the powers they supply, to action proportioned to nature, why should we grope among the dry bones of the past, or put the living generation into masquerade out of its faded wardrobe? The sun shines to-day also. There is more wool and flax in the fields. There are new lands, new men, new thoughts. Let us demand our own works and laws and worship. Paraphrase Glossary Modern connectionThis feels like a critique of living secondhand — relying on past voices, recycled ideas, and inherited beliefs instead of direct experience. It’s like endlessly quoting experts, influencers, or traditions while rarely asking what you actually see, think, or feel. It pushes back against nostalgia and intellectual hand-me-downs. Just because something is old, established, or revered doesn’t mean it’s more alive or more true for the present moment. Each generation faces a different world and needs its own ways of understanding it. There’s also an energizing call to participate in life now, not just study it. Instead of curating the past, create something that belongs to your time — new art, new questions, new forms of meaning. The idea is that insight isn’t extinct; it’s available in the present, if people trust their own perception enough to look. Paragraph 2: But to a sound judgment, the most abstract truth is the most practical. Whenever a true theory appears, it will be its own evidence. Its test is, that it will explain all phenomena. Now many are thought not only unexplained but inexplicable; as language, sleep, madness, dreams, beasts, sex. Paraphrase There are still many aspects of life that people find mysterious or even impossible to explain — like how language works, why we sleep, the nature of madness, dreams, animals, or sexual instincts — but a genuinely true idea will begin to illuminate even these phenomena. Glossary Modern connectionThis connects to the idea that the deepest principles often turn out to be the most useful. A powerful insight isn’t just intellectually impressive — it suddenly makes lots of different things make sense at once. When a theory is truly solid, it simplifies the world instead of complicating it. It also challenges the habit of labeling parts of life as “mysteries” and leaving them there. Areas like the mind, identity, instinct, or altered states can seem chaotic or unknowable, but this perspective assumes they do fit into a larger pattern — we just haven’t found the right lens yet. In modern terms, it’s the mindset behind big unifying ideas in psychology, science, and philosophy: the belief that even the strangest parts of human experience aren’t random glitches, but meaningful pieces of a coherent whole waiting to be understood. Paragraph 3: Philosophically considered, the universe is composed of Nature and the Soul. Strictly speaking, therefore, all that is separate from us, all which Philosophy distinguishes as the NOT ME, that is, both nature and art, all other men and my own body, must be ranked under this name, Nature. Paragraph 4: In enumerating the values of nature and casting up their sum, I shall use the word in both senses; in its common and in its philosophical import. In inquiries so general as our present one, the inaccuracy is not material; no confusion of thought will occur. Paraphrase Strictly speaking, anything we experience as separate from our inner awareness — anything that can be called “not me” — belongs to Nature. This includes not only forests, rivers, and stars, but also human-made things, other people, and even our own physical body. All of these are objects of perception, things we can observe, and in that sense they stand outside the core self. As Emerson goes on to describe the value and meaning of nature, he explains that he will use the word “nature” in both its everyday sense (the natural world around us) and in this broader philosophical sense (everything that is “not me”). Since the discussion is very general and wide-ranging, this double meaning won’t cause serious confusion. Exact precision isn’t crucial here, and the overall idea will remain clear. Glossary Modern connectionThis reflects the idea that we experience life through a basic split: the inner world of awareness and the outer world of everything we perceive — including our own bodies. It’s similar to how people today talk about “subjective experience” versus “objective reality,” even while recognizing the boundary between them isn’t always clear. It also mirrors modern discussions in psychology and philosophy about how much of what we call “the world” is filtered through perception. What feels external and solid is always being interpreted by an inner consciousness, so the line between observer and environment is more fluid than it seems. At the same time, there’s a practical attitude here: when exploring big, foundational questions, we sometimes need flexible language rather than rigid definitions. In modern terms, it’s like saying, “Let’s not get stuck on terminology — the point is to understand the relationship between mind and world, not to win a vocabulary debate.” Paragraph 5: Nature, in the common sense, refers to essences unchanged by man; space, the air, the river, the leaf. Art is applied to the mixture of his will with the same things, as in a house, a canal, a statue, a picture. But his operations taken together are so insignificant, a little chipping, baking, patching, and washing, that in an impression so grand as that of the world on the human mind, they do not vary the result. Chapter I — NatureParagraph 6: To go into solitude, a man needs to retire as much from his chamber as from society. I am not solitary whilst I read and write, though nobody is with me. But if a man would be alone, let him look at the stars. The rays that come from those heavenly worlds will separate between him and what he touches. One might think the atmosphere was made transparent with this design, to give man, in the heavenly bodies, the perpetual presence of the sublime. Seen in the streets of cities, how great they are! If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore; and preserve for many generations the remembrance of the city of God which had been shown! But every night come out these envoys of beauty, and light the universe with their admonishing smile. Paragraph 7: The stars awaken a certain reverence, because though always present, they are inaccessible; but all natural objects make a kindred impression, when the mind is open to their influence. Nature never wears a mean appearance. Neither does the wisest man extort her secret, and lose his curiosity by finding out all her perfection. Nature never becomes a toy to a wise spirit. The flowers, the animals, the mountains, reflected the wisdom of his best hour, as much as they had delighted the simplicity of his childhood. Paraphrase When Emerson begins his first chapter on Nature, he turns to the experience of solitude. To truly be alone, a person must withdraw not only from other people but even from the distractions of his own room. You’re not really solitary if you’re reading or writing, even if no one else is present. But if someone truly wants to feel alone, they should look at the stars. The light coming from distant worlds creates a sense of separation between the observer and everything close at hand. It almost seems as if the atmosphere were made transparent on purpose, so that human beings could always see these heavenly bodies and feel the constant presence of something sublime. In the middle of a city street, the stars still appear majestic. If they showed themselves only once every thousand years, people would be overwhelmed with awe, worship them, and pass down stories for generations about the divine vision they had witnessed. Yet these messengers of beauty appear every night, quietly lighting up the sky and offering their gentle, instructive smile. The stars inspire reverence because, although we see them regularly, we can never reach them. But all natural objects can create a similar feeling, as long as the mind is open and receptive. Nature never appears trivial or cheap. Even the wisest person cannot fully uncover all her secrets or lose their sense of wonder by understanding everything about her. Nature never becomes a mere plaything for a thoughtful, mature spirit. Flowers, animals, and mountains reflect the deep insight of a person’s best and wisest moments just as much as they delighted that same person in the innocent simplicity of childhood.

Glossary Modern connectionThis speaks to how small human alterations can feel enormous to us but are tiny against the scale of the larger world. It’s a reminder that despite all our construction, technology, and design, we still live inside forces and environments we didn’t create and don’t control. That perspective can shrink the ego a little and restore a sense of proportion. It also redefines solitude. Being physically alone isn’t the same as being mentally separate from noise, distraction, and social input. Real solitude today might mean stepping away from screens, information streams, and constant communication long enough to feel yourself as a distinct presence in a vast world. The night sky example translates easily into modern life: we become numb to wonder through overexposure. What is constantly available often gets ignored, even if it’s extraordinary. Rarity creates reverence, but the deeper invitation is to recover awe without needing scarcity — to notice the extraordinary in what appears every day. There’s also the idea that nature — or simply the non-human world — has a stabilizing effect on the mind when we’re receptive. People still report that time outdoors clears mental clutter, restores perspective, and reawakens curiosity that routine and productivity culture tend to dull. Finally, this suggests that wisdom doesn’t outgrow wonder. Maturity doesn’t have to mean becoming unimpressed or overly analytical. A healthy, fully developed mind can be just as moved by simple, natural things as a child is — but with deeper awareness rather than naïveté. Paragraph 8: When we speak of nature in this manner, we have a distinct but most poetical sense in the mind. We mean the integrity of impression made by manifold natural objects. It is this which distinguishes the stick of timber of the wood-cutter, from the tree of the poet. The charming landscape which I saw this morning, is indubitably made up of some twenty or thirty farms. Miller owns this field, Locke that, and Manning the woodland beyond. But none of them owns the landscape. There is a property in the horizon which no man has but he whose eye can integrate all the parts, that is, the poet. This is the best part of these men’s farms, yet to this their warranty-deeds give no title. Paragraph 9: The sun illuminates only the eye of the man, but shines into the eye and the heart of the child. The lover of nature is he whose inward and outward senses are still truly adjusted to each other; who has retained the spirit of infancy even into the era of manhood. His intercourse with heaven and earth becomes part of his daily food.

ChatGPT: This is a gorgeous and important turn in the essay. Paraphrase The beautiful landscape I admired this morning is technically made up of many separate farms. One person owns one field, another owns the next, and someone else owns the woods beyond. But none of them actually owns the landscape itself. The horizon — the total, harmonious view — belongs only to the person whose perception can gather all the parts into a single whole. That person is the poet. And this unified beauty is the finest aspect of those farms, yet no legal document can grant ownership of it.

The sun doesn’t just light up a person’s eyes in a physical sense; for a child, its light reaches both the eyes and the heart. A true lover of nature is someone whose inner feelings and outer senses are still in balance and harmony. Such a person has carried the spirit of childhood — openness, wonder, and direct feeling — forward into adulthood. For them, their connection with heaven and earth becomes as natural and necessary as daily nourishment. Glossary This is Emerson saying that wholeness of perception, not legal ownership, is what truly “possesses” nature — and that the mature soul can regain the child’s living connection to the world. Modern connectionThis reflects the difference between seeing the world as raw material versus experiencing it as meaning. Two people can look at the same place — one sees resources, property lines, and practical use; the other feels mood, beauty, and emotional resonance. The “landscape” isn’t just physical — it’s something created in perception. It also points to a kind of ownership that has nothing to do with legal possession. The deepest experience of something — a view, a moment, a piece of music — belongs to the person who can truly take it in. Attention becomes a form of participation that’s richer than control. The contrast between the adult and the child speaks to a quality many people feel they’ve lost: the ability to be fully struck by simple things. Growing up often means becoming efficient, analytical, and distracted, but also less permeable to wonder. This idea suggests maturity doesn’t have to dull perception — the goal is to keep inner sensitivity aligned with outward experience. In modern life, that might look like resisting constant mental noise long enough to actually register where you are, what you’re seeing, and how it affects you. When perception is alive in that way, everyday surroundings stop feeling flat and start feeling quietly nourishing — not as escape, but as a steady source of renewal. Paragraph 10: In the presence of nature, a wild delight runs through the man, in spite of real sorrows. Nature says,—he is my creature, and maugre all his impertinent griefs, he shall be glad with me. Not the sun or the summer alone, but every hour and season yields its tribute of delight; for every hour and change corresponds to and authorizes a different state of the mind, from breathless noon to grimmest midnight. Paragraph 11: Nature is a setting that fits equally well a comic or a mourning piece. In good health, the air is a cordial of incredible virtue. Crossing a bare common, in snow-puddles, at twilight, under a clouded sky, without having in my thoughts any occurrence of special good fortune, I have enjoyed a perfect exhilaration. I am glad to the brink of fear. Paragraph 12: In the woods, too, a man casts off his years, as the snake his slough, and at what period soever of life is always a child. In the woods is perpetual youth. Within these plantations of God, a decorum and sanctity reign; a perennial festival is dressed, and the guest sees not how he should tire of them in a thousand years. Paragraph 13: In the woods, we return to reason and faith. There I feel that nothing can befall me in life,—no disgrace, no calamity, (leaving me my eyes,) which nature cannot repair. Standing on the bare ground,—my head bathed by the blithe air, and uplifted into infinite space,—all mean egotism vanishes. ChatGPT: This is Emerson at full lyrical power — joy, healing, and the dissolving of the ego. Here’s the combined paraphrase and glossary. Paraphrase Not only sunny summer days, but every hour and every season brings its own kind of pleasure. Each time of day and change in weather matches a different mood of the mind, from the still intensity of noon to the dark solemnity of midnight. Nature provides a backdrop that suits every human emotion, whether joyful or sorrowful. When we are healthy, the air itself feels like a powerful, life-giving tonic. Emerson describes walking across an open field in slushy snow at twilight under a cloudy sky — not thinking about any special good news — yet feeling a pure rush of happiness. The feeling is so strong it almost becomes overwhelming, as if joy itself could tip into fear. In the woods, we shed the weight of age the way a snake sheds its old skin, and no matter how old we are, we feel young again. The forest is a place of constant youth. In these “plantations of God” — these natural groves — there is a sense of order, dignity, and sacredness. Nature feels like an endless celebration, and a visitor can’t imagine ever growing tired of it, even over thousands of years. In the woods, we recover our sense of reason and faith. There, Emerson feels that no trouble in life — no shame or disaster, as long as he still has his sight — is beyond nature’s power to heal. Standing directly on the earth, with fresh air on his face and the vast sky above him, all petty self-centeredness disappears. Glossary We’re right on the edge now of the famous “transparent eyeball” passage — the moment where the self thins out completely into pure perception. Modern connectionThis captures the strange way the natural world can lift mood even when nothing in your personal circumstances has changed. A walk outside, shifting light, cold air, or open space can cut through mental heaviness and remind you that your inner weather isn’t the only reality. It also suggests that environments don’t come pre-labeled with emotional meaning — they hold space for whatever you bring, whether joy or grief. The same landscape can feel consoling, energizing, or solemn depending on your state of mind, almost like a silent companion rather than a backdrop. There’s a powerful idea here about renewal. Stepping into certain spaces can make you feel temporarily freed from age, roles, and accumulated stress — less like a résumé and more like a living being again. That reset doesn’t come from distraction but from contact with something that isn’t shaped by human urgency. Finally, it points to a loosening of self-importance. In wide, open settings, personal worries can shrink to more human proportions. Problems don’t necessarily disappear, but they stop feeling like the whole universe. Perspective returns, along with a quiet trust that life is larger than any single setback. Paragraph 14: I become a transparent eyeball; I am nothing; I see all; the currents of the Universal Being circulate through me; I am part or particle of God. Paragraph 15: The name of the nearest friend sounds then foreign and accidental: to be brothers, to be acquaintances,—master or servant,—is then a trifle and a disturbance. I am the lover of uncontained and immortal beauty. Paragraph 16: In the wilderness, I find something more dear and connate than in streets or villages. In the tranquil landscape, and especially in the distant line of the horizon, man beholds somewhat as beautiful as his own nature. Paragraph 17: The greatest delight which the fields and woods minister, is the suggestion of an occult relation between man and the vegetable. I am not alone and unacknowledged. They nod to me, and I to them. ChatGPT: This is the mystical summit of the chapter. Let’s walk it carefully. Paraphrase His individual ego fades away, yet his perception expands to take in everything. He feels the life force of the universe flowing through him, and experiences himself as a small part of the divine whole. In that moment, ordinary social identities lose their importance. The name of even a close friend feels distant and unessential. Roles like brother, acquaintance, master, or servant seem trivial and distracting. Instead, he feels himself to be a lover of boundless and eternal beauty — a beauty that cannot be confined by social categories or personal relationships. Out in the wilderness, Emerson feels a deeper kinship than he does in towns or cities. In a peaceful natural scene — especially when gazing at the far horizon — a person sees something that mirrors the beauty of their own inner nature. The outer world reflects the inner self. One of the greatest joys the natural world offers is the sense of a hidden, mysterious connection between human beings and plant life. Emerson feels recognized and acknowledged by nature. He is not alone. The plants seem to greet him, and he responds in return, as if there were a silent mutual understanding between them.

Glossary Here Emerson fully crosses from appreciating nature into unity with being itself — where self, nature, and God are no longer separate. Next comes his turn back toward ordinary perception again — but changed.

Modern connectionThis points to moments when the sense of being a separate, self-enclosed individual softens, and awareness feels wider and less centered on “me.” People describe this in meditation, peak experiences, art, or time in vast natural settings — a feeling of observing without the usual mental commentary or self-story running the show. In those states, social roles and labels can seem oddly superficial. Status, obligations, and even personal history fade into the background, replaced by a stronger pull toward beauty, presence, and a sense of belonging to something larger than human structures. There’s also the experience of feeling more at home in open, unstructured environments than in built, crowded ones. Wide horizons and quiet landscapes can mirror an inner spaciousness, as if the outer scene matches something essential in us that daily routines often compress. Finally, this suggests a felt kinship with the living world — not as a poetic metaphor but as an emotional intuition. Many people experience a subtle sense of companionship in natural settings, as if being surrounded by life that doesn’t judge, demand, or ignore them. It can ease loneliness in a way social contact sometimes doesn’t, because it touches a deeper layer of connection. Paragraph 18: The waving of the boughs in the storm is new to me and old. It takes me by surprise, and yet is not unknown. Its effect is like that of a higher thought or a better emotion coming over me, when I deemed I was thinking justly or doing right. Paragraph 19: Yet it is certain that the power to produce this delight does not reside in nature, but in man, or in a harmony of both. It is necessary to use these pleasures with great temperance. For nature is not always tricked in holiday attire, but the same scene which yesterday breathed perfume and glittered as for the frolic of the nymphs, is overspread with melancholy today. Paragraph 20: The lover of nature in all his moods, and at all times, sees the cause of every event, the meaning of every occurrence, the law of every object, the end of every being. The earth is not a dead mass, but a living power; and what we call accidental is the necessity of a higher order. The stones, the rivers, the trees, the mountains, each have a story to tell; and to him who knows how to read, there is a message in every leaf and a revelation in every wind. Paraphrase However, the delight we feel in nature doesn’t come from nature alone. It arises from us — from our perception, or from the interaction between ourselves and the natural world. We must approach these pleasures with balance and restraint. Nature is not always dressed up to entertain us. The same scene that yesterday seemed alive, fragrant, and playful may today appear somber or melancholy. The beauty we perceive depends both on the world and on the state of our own minds. A true lover of nature, in all moods and at all times, recognizes the cause behind each event, the meaning in every occurrence, the law underlying every object, and the purpose of every being. The earth is not dead or inert; it is a living, active power. What seems accidental or random is actually part of a higher order. Every stone, river, tree, and mountain tells a story. For those who know how to read the signs, every leaf carries a message and every breeze carries a revelation. The natural world is a text written in light, form, and sound, waiting for the attentive eye and receptive mind. Glossary This section deepens Emerson’s point that nature alone is not enough — the inner life, the perceptive soul, is what makes the world intelligible, beautiful, and meaningful. The interaction between observer and observed is what produces delight, insight, and revelation. Modern connectionThis highlights how moments of awe or insight often feel both surprising and familiar, like recognizing a truth you didn’t know you knew. In modern terms, it’s the sudden clarity that comes in reflection, meditation, or creative flow — when a new idea or emotion arrives just as you need it. It also reminds us that joy in the world isn’t automatic; it depends on our own perception and openness. Nature—or any experience—doesn’t guarantee happiness, but it can catalyze it when we’re receptive. The same environment can inspire wonder one day and melancholy the next, depending on our inner state. Finally, it frames life as a network of meaning rather than random chaos. Modernly, this is like seeing patterns in systems, relationships, or personal experience: everything has a context and purpose, and if we pay attention, even ordinary moments carry messages. It’s a call to cultivate awareness so that life feels alive, rich, and instructive, rather than flat and accidental. Paragraph 21: The influence of nature never ceases. Its forms, sounds, colors, and motions act upon the senses and the mind. The forest and the mountain, the sea and the sky, are all educators, shaping the character, stimulating the intellect, and elevating the soul. The wise man opens his heart and his senses, and, through the outward world, he perceives the inward; through the visible, he apprehends the invisible. Paragraph 22: The universe is composed of Nature and the Soul; but these are not severed. Nature, as a material world, is the body of the spirit; the soul is the life within it. In man, the harmony between these two is realized; and every step in knowledge and virtue is a step in the unison of the outward and the inward. Paragraph 23: We cannot fully appreciate or enjoy nature until we understand our own nature. Self-reliance, self-knowledge, and the cultivation of our own powers are prerequisites to the true perception of the world. As the eye cannot see without light, so the mind cannot comprehend the universe without the illumination of the soul. Paraphrase The universe consists of Nature and the Soul, but these are not separate. Nature, as the material world, is like the body of spirit; the soul is the life force within it. In human beings, the harmony between the outward and the inward is realized. Every step we take in understanding and virtue is a step toward uniting the material and spiritual sides of life — toward perfect correspondence between what we perceive outside and what lives within. We cannot truly appreciate or enjoy nature until we understand our own inner nature. Self-reliance, self-knowledge, and the careful cultivation of our abilities are prerequisites for genuinely seeing the world. Just as the eye cannot see without light, the mind cannot fully comprehend the universe without the illumination of the soul. Glossary Emerson here is clearly emphasizing that nature and soul are intertwined, and that true perception requires an awakened, self-aware inner life. Observing the external world becomes meaningful only when the inner eye is illuminated. Modern connectionThis emphasizes that the world around us is constantly teaching and shaping us, if we are attentive. Modernly, it’s like noticing how experiences, environments, and even design influence mood, thinking, and character — nature, art, or any rich setting can act as a subtle guide for growth. It also stresses the integration of inner and outer life. True understanding or progress isn’t just about observing the world or developing skills in isolation; it comes from aligning perception, thought, and action with a deeper self-awareness. In modern terms, this mirrors ideas in mindfulness, emotional intelligence, and holistic personal development. Finally, it reminds us that self-knowledge is the lens for perceiving reality. Just as vision needs light, comprehension requires inner illumination: knowing yourself — your tendencies, values, and capacities — is essential for truly engaging with the world rather than skimming its surface. Chapter II — CommodityParagraph 24: Nature is useful to man. It ministers to his bodily necessities, supplies his wants, and renders life comfortable. The earth bears bread for him; the rivers, fish; the forests, wood; the pastures, herds; and the skies, rain. Man relies on these gifts, and in his prosperity forgets the source. Yet every necessity supplied by nature is a link between the visible world and the spirit of man; for his life is sustained by the laws of the universe, and every material good is a testimony of divine order. Paragraph 25: The material universe is not independent of the soul; the usefulness of nature is itself a form of beauty. A tree yields fruit, but it also charms the eye; a river quenches thirst, but it delights the imagination; a field produces grain, but it inspires meditation. All commodities are thus both practical and moral; they are means and symbols, service and revelation. Paragraph 26: The scholar may reason, and the artisan may labor; but all alike depend upon nature’s bounty. The wisdom of man consists not merely in extracting advantage, but in perceiving that every object, from the rock to the star, is in its place for the instruction, the pleasure, and the improvement of the soul. Paragraph 27: The uses of nature are infinite; they extend to the body, to the mind, and to the spirit. They teach industry and frugality; they awaken invention and art; they cultivate patience, vigilance, and strength; and they inspire gratitude and reverence. In this respect, nature is the grand teacher and the great benefactor. Paraphrase But nature’s usefulness is not separate from beauty. A tree produces fruit, but it also pleases the eye; a river gives water, yet it stimulates the imagination; a field grows grain, yet it invites meditation. Practical objects are also moral and symbolic — they serve a function and reveal something deeper. They are both service and revelation. Whether a scholar studies or an artisan works, all people depend on nature’s abundance. Human wisdom is not just about taking advantage of resources, but about perceiving that every object — from the smallest rock to the distant stars — exists in its place to instruct, delight, and elevate the soul. Nature’s usefulness is infinite, affecting body, mind, and spirit. It teaches industriousness and carefulness, sparks invention and artistic creation, cultivates patience, vigilance, and strength, and inspires gratitude and reverence. In this way, nature is the grand teacher and the great benefactor of humanity. Glossary Here Emerson emphasizes that practical utility and spiritual beauty are inseparable — every part of nature serves both the body and the soul. We can move on to Paragraph 28 and beyond, where he shifts into the philosophical and moral reflections on Nature’s law and influence. Modern connectionThis highlights how the practical benefits of the world around us — food, water, materials, energy — are inseparable from their deeper significance. In modern terms, it’s the idea that resources, technology, or infrastructure aren’t just utilitarian; they also shape culture, imagination, and ethical reflection. It also frames usefulness as a form of beauty. When something serves both practical and aesthetic purposes, it becomes a teacher and a guide. Everyday objects, environments, and systems can inspire creativity, thoughtfulness, and gratitude if we pay attention. Finally, it’s a reminder that no one operates in isolation. Whether scholar, worker, or innovator, everyone depends on larger systems — ecological, social, or material. Recognizing that interdependence fosters humility, responsibility, and an appreciation for the broader intelligence and order embedded in life. Chapter III — BeautyParagraph 28: Nature always wears the colors of the spirit. To a man laboring under calamity, the heat of his own fire and the warmth of his own day are welcome, and the landscape wears the hues of his thought. The soul grows faint, and the world appears dull; it rises, and the world awakens in beauty. Paragraph 29: Beauty is the expression of the highest law. All things are beautiful, as far as they express harmony, proportion, and fitness. A tree, a flower, a mountain, a cloud, each is perfect when it realizes its design. Man feels this perfection, and is inspired to imitation, praise, and love. Paragraph 30: The perception of beauty is a moral act. It is the recognition of truth in form, and of spirit in matter. Nature delights, elevates, and ennobles, because it is the mirror of the divine. Through beauty, the soul apprehends the eternal order, and participates in the joy of creation. Paragraph 31: The beautiful in nature, therefore, is a revelation, a symbol, a language; and man, in contemplating it, is both observer and interpreter. The artist, the poet, and the philosopher all seek to reveal this beauty, and, in doing so, make it accessible to others. Paraphrase Beauty is the outward expression of the highest natural law. Everything is beautiful to the extent that it embodies harmony, proportion, and fitness for its purpose. A tree, a flower, a mountain, or a cloud is perfect when it fulfills its design. Human beings sense this perfection and are moved to imitate, admire, and love. Recognizing beauty is a moral act. It is the acknowledgment of truth in form and the presence of spirit in matter. Nature delights, uplifts, and ennobles the soul because it mirrors the divine. Through encounters with beauty, the soul grasps the eternal order and participates in the joy of creation. Therefore, the beautiful in nature functions as a revelation, a symbol, and a language. Humans, in observing it, act as both witnesses and interpreters. Artists, poets, and philosophers strive to reveal this beauty, making it accessible for others to experience and understand.

Glossary Emerson is emphasizing here that beauty is both practical and spiritual, a bridge between nature and the human soul, and that perceiving it is itself an ethical and elevating act. We can move on to Paragraph 32 onward, where he begins connecting these observations to morality and practical philosophy. Modern connectionThis highlights how our inner state shapes the way we experience the world — a gloomy mood can dull perception, while a lifted spirit can make even ordinary surroundings radiant. In modern terms, it’s the psychology of perception: our emotions and mindset literally color our experience. It also frames beauty as more than decoration or pleasure; it’s a signal of harmony, proportion, and purpose. Recognizing beauty trains the mind to notice order and inspires creativity, imitation, and ethical reflection. Finally, perceiving beauty becomes an active, even moral, engagement. Whether in art, design, or everyday observation, noticing and sharing what is beautiful connects us to larger patterns and meaning, fostering both personal growth and communal appreciation of the world. Chapter IV — LanguageParagraph 32: Language is the representation of thought; and thought is born of the experience of nature. Words are signs of natural facts, and through them we communicate the wisdom gained from observation. All human speech is thus, at bottom, a record of the impressions made by the external world upon the mind. Paragraph 33: Words, like tools, are derived from the forms and functions of nature. Names of objects, of qualities, of actions, and of relations, are but translations of sensible appearances into vocal symbols. The poet, recognizing the law of analogy, may extend this language to spiritual and abstract truths, conveying the invisible through the visible. Paragraph 34: All human knowledge rests on this process. From simple observation to complex philosophy, from the names of trees to the principles of government, the chain of ideas is linked by the correspondence between outward signs and inward realities. In this sense, language is a part of nature; it is the medium through which man interprets, communicates, and perpetuates the lessons of the universe. Paraphrase Words function like tools, shaped by nature’s forms and purposes. Names for objects, qualities, actions, and relationships are translations of what we sense in the world into vocal signs. A poet, recognizing patterns and analogies in nature, can extend this system of language to express spiritual or abstract truths — using the visible world as a bridge to convey the invisible. All human knowledge depends on this process. From the simplest observations to the most elaborate philosophies, from naming a tree to developing principles of governance, our ideas are linked by the correspondence between outward signs and inner realities. Language itself is part of nature; it is the medium through which humans interpret the universe, communicate their discoveries, and pass on the lessons of experience across generations. Glossary Emerson here is connecting language, perception, and moral-spiritual insight. Our words are grounded in experience, and poetry or philosophy extends them to reveal deeper truths, making the invisible intelligible through the visible world. We can continue with Paragraph 35 next, which moves toward the individual and society. Modern connectionThis shows that language isn’t just arbitrary — it’s grounded in our experience of the world. Modernly, it’s like saying all communication ultimately reflects observation, interaction, and pattern recognition: words, symbols, and even digital media are tools to translate experience into shared understanding. It also highlights the creative power of language. Just as tools extend physical ability, words extend thought, allowing us to express abstract, spiritual, or complex ideas by linking them to familiar experiences. Finally, it frames knowledge as a chain connecting perception, interpretation, and communication. Science, philosophy, art, and everyday conversation all rely on translating reality into symbols. In modern terms, language is both a map and a bridge — a way to make sense of the world and share that sense with others.

Chapter V — DisciplineParagraph 35: The discipline of nature is the discipline of the soul. The forces that act upon the body also act upon the mind. The same laws which guide the movement of the stars, and the growth of trees, operate in the development of thought, habit, and character. Every circumstance, every trial, every pleasure, is a part of this system of discipline. Paragraph 36: Nature does not hurry, yet everything is accomplished. The tides, the seasons, the rivers, and the clouds follow their appointed courses without error or neglect. Man, in observing these, learns patience, perseverance, and regularity. The discipline of the outward world becomes a mirror of the order within, and the soul harmonizes with universal law. Paragraph 37: No man can fully understand himself or his duties without observing the order and sequence of events in the natural world. Every leaf, every flower, every insect, and every star is a lesson. To neglect them is to neglect instruction of the highest value; to attend to them is to gain insight into the principles that govern life. Paragraph 38: In the discipline of nature, there is no coercion; only opportunity, suggestion, and encouragement. The mind is trained not by force, but by participation. The beauty, the order, and the harmony of the universe awaken similar qualities in the soul, and the individual grows in proportion to his perception and acceptance of these influences. Paraphrase Nature never rushes, yet everything reaches completion in its appointed time. The tides rise and fall, the seasons change, rivers flow, and clouds drift along their paths without error. Observing these patterns teaches humans patience, perseverance, and regularity. The rhythms of the external world reflect an inner order, and as we attune ourselves to them, the soul comes into harmony with universal law. No one can fully understand themselves or their responsibilities without noticing the sequence and order in the natural world. Every leaf, flower, insect, and star carries a lesson. Ignoring these signs is ignoring the highest form of instruction; paying attention brings insight into the principles that govern life and existence. In nature’s discipline, there is no coercion or force. The mind learns through opportunity, suggestion, and gentle encouragement. By participating in nature — observing its beauty, order, and harmony — the soul is trained. The individual grows in proportion to their perception and acceptance of these influences, becoming stronger, wiser, and more aligned with the universe. Glossary Emerson here emphasizes that every aspect of nature is simultaneously practical, moral, and spiritual training for the soul. By observing and aligning with these patterns, a person cultivates inner order, patience, and growth — a clear bridge between outer perception and inner spaciousness. We can continue with Paragraph 39 and onward, where Emerson moves into reflection on human society and the mind’s relation to the natural world. Modern connectionThis emphasizes that the world around us functions as both teacher and mirror. Observing natural rhythms — seasons, tides, growth, and change — can cultivate patience, discipline, and an intuitive understanding of life’s patterns. Modernly, it’s like learning resilience and self-mastery from systems and processes rather than from force or instruction alone. It also frames learning as participation rather than coercion. We grow by engaging with our environment and noticing its order and harmony, not by being pushed or pressured. Finally, it suggests that insight, character, and self-knowledge emerge from attentive observation. The same patterns that guide rivers, stars, and trees can guide thought, habit, and moral development if we take the time to see them — a reminder that life’s lessons are embedded in everyday experience. Chapter VI — IdealismParagraph 39: Nature is an emblem of the spirit. Every visible object is a symbol of some inward truth. The material world is an image of the mind; the heavens reflect the soul. Every fact and every object invites interpretation. The ideal resides within; nature mirrors it without. Paragraph 40: The idealist sees in the simplest natural form a representation of the eternal. The blade of grass, the tree, the cloud, the rock, all signify principles of harmony, order, and power. Nature is not mere matter, but the embodiment of thought. Paragraph 41: Through idealism, man transcends the senses, and attains the knowledge of the spiritual in the material. The mind interprets appearances, sees beyond phenomena, and discerns the law behind events. To the idealist, every circumstance is full of instruction; every object is a teacher; every relation is significant. Paragraph 42: Nature without idealism is blindness; idealism without nature is vain. Only in their union does man perceive truth. The eye that sees the outward world with the inward vision gains knowledge, delight, and power.

Paraphrase The idealist perceives eternal truths even in the simplest elements of nature. A blade of grass, a tree, a cloud, or a rock can reveal principles of harmony, order, and power. Nature is not just raw matter; it embodies thought and meaning. Through this idealism, humans transcend mere sensory experience and access knowledge of spiritual reality through the material world. The mind interprets appearances, looks beyond phenomena, and understands the laws underlying events. For the idealist, every situation contains instruction, every object is a teacher, and every relationship carries significance. Nature without idealism is blindness, and idealism without nature is empty or vain. Only when the two are united can humans truly perceive truth. Those who see the outer world with inward vision gain knowledge, joy, and the power to act rightly in accordance with universal principles. Glossary Here Emerson is emphasizing that truth and spiritual knowledge emerge only when the material world is read through the lens of the mind and soul. Nature is a mirror, but without idealism, that mirror is opaque. Likewise, idealism must connect to the real world, or it floats without grounding. We can continue with Paragraph 43 onward, where Emerson explores the interplay of nature, man, and society. Modern connectionThis emphasizes that the world around us is more than a collection of objects — it’s a reflection of ideas, principles, and values. In modern terms, it’s the mindset that looks for meaning and patterns in everyday life, seeing lessons and inspiration in both the ordinary and the extraordinary. It also highlights the role of imagination and interpretation. Facts, events, and experiences are amplified when the mind actively connects them to larger truths, much like creativity, philosophy, or critical thinking transforms raw information into insight. Finally, it points to balance: awareness without reflection is shallow, and reflection without experience is empty. True understanding comes when perception and interpretation work together — when we see the outer world with the inner eye, we gain clarity, motivation, and a deeper sense of connection. Chapter VII — SpiritParagraph 43: The spirit of man is in sympathy with the spirit of nature. The laws that govern the stars, the tides, and the growth of plants, govern thought, feeling, and action. The soul is part of the universal spirit; and its growth, health, and beauty depend on harmony with the greater life around it. Paragraph 44: Man’s faculties are developed by intercourse with nature. The understanding learns from the order of events; the imagination is awakened by the beauty of forms; the moral sense is strengthened by the regularity, harmony, and beneficence of natural law. Thus the spirit of man is disciplined and elevated by observation and contemplation. Paragraph 45: The universe is friendly to the development of genius. Every part of creation contributes to the education of man; and the soul that is awake perceives the divine purpose in all things. To live in harmony with nature is to participate in the eternal; to resist it is to resist the laws of life itself. ChatGPT: Here Emerson is really braiding cosmos, mind, and moral life into one fabric. Paraphrase Our mental and spiritual abilities develop through our interaction with nature. The intellect learns from observing the order and sequence of events in the natural world. The imagination is stirred by the beauty of shapes, colors, and landscapes. The moral sense — our sense of rightness and goodness — is strengthened by witnessing the regularity, balance, and generosity built into natural law. In this way, by observing and reflecting on nature, the human spirit is trained, refined, and lifted to a higher level. The universe itself supports the growth of human greatness. Everything in creation plays a role in educating the soul. A person who is spiritually awake can perceive a divine intention woven through all things. To live in harmony with nature is to share in what is eternal and universal; to live against it is to oppose the very principles that make life possible. Glossary Here Emerson is making a huge claim: self-cultivation is not separate from cosmology. To grow mentally, imaginatively, and morally is literally to come into alignment with the structure of the universe itself — which, in his terms, means alignment with the Over-Soul expressed through nature. Modern connectionThis emphasizes that personal growth is deeply connected to the environment around us. In modern terms, it’s the idea that our thinking, creativity, and ethics are shaped by exposure to order, beauty, and patterns in the world — whether in nature, systems, or well-designed experiences. It also highlights learning through participation and observation. Insight, imagination, and moral awareness develop not in isolation but by engaging with the larger rhythms and structures that surround us. Finally, it frames the universe as a supportive context for growth. Life is most nourishing when we align with its patterns and laws; resistance or disconnection from those rhythms can stunt understanding, creativity, and fulfillment. In essence, thriving comes from tuning oneself to the currents of the larger world. Chapter VIII — ProspectsParagraph 46: The future is not hidden; it is disclosed in the present. The course of events, the forms of life, and the progression of society are all signs of what is to come. Man, in observing nature and society, perceives tendencies, opportunities, and duties. The law of the universe is constant, and its purposes are manifest in the unfolding of life. Paragraph 47: The individual who trusts in nature, who seeks communion with its laws, and who interprets its symbols aright, will find guidance in every circumstance. He will see the world not as a chaos, but as an ordered, intelligent system; not as a prison, but as a school; not as an accident, but as a revelation. Paragraph 48: The highest prospect of man is union with the universal spirit. In knowledge, in virtue, in beauty, he participates in the life of the universe. By study, reflection, and action, he becomes a part of the order he contemplates, and finds in every experience a testimony to the wisdom and benevolence of God. Paragraph 49: Thus, in all time, nature continues to teach, to elevate, and to inspire. The student of her laws perceives that the material and the spiritual, the temporal and the eternal, are not separate; and he walks through life in the company of wisdom, beauty, and power. ChatGPT: You can feel Emerson lifting the lens here from personal insight to a kind of cosmic orientation — how to live in time while rooted in the eternal. Paraphrase A person who trusts nature, seeks to live in harmony with its laws, and correctly understands its symbols will find guidance in every situation. Such a person no longer sees the world as random confusion, but as an ordered and intelligent whole. Life does not appear as a trap or punishment, but as a place of learning. Events do not seem accidental, but meaningful — part of an ongoing revelation of deeper truth. The highest destiny of a human being is union with the universal spirit. In gaining knowledge, practicing virtue, and appreciating beauty, a person shares in the life of the whole universe. Through study, reflection, and right action, one becomes integrated into the very order one observes. Every experience then becomes evidence of divine wisdom and goodness at work in the world. So, at all times, nature continues its role as teacher, uplifter, and source of inspiration. Those who study its laws come to understand that matter and spirit, time and eternity, are not truly separate. Such a person moves through life accompanied by wisdom, beauty, and a sense of inward strength. Glossary This is Emerson at full stride: if we read the present deeply enough, we begin to live as guided from within the flow of the whole. Modern connectionThis emphasizes that the present contains clues about the future. In modern terms, it’s like reading trends, observing systems, or noticing patterns in daily life — small signals can reveal larger opportunities, risks, or directions. It also frames the world as an intelligible, ordered system rather than random chaos. When we pay attention, even ordinary events can teach lessons, reveal principles, and guide decisions. Finally, it highlights the idea of alignment and participation. Growth, fulfillment, and insight come from engaging thoughtfully with the world’s patterns, cultivating knowledge, virtue, and creativity. By observing, reflecting, and acting, we connect with larger forces, finding purpose and inspiration in both everyday life and the broader sweep of existence. Brief paraphrase of the entire essay Emerson begins by challenging us to see the world directly, rather than through the eyes of tradition or past generations. He insists that each person can experience an original relation to the universe, and that nature offers a living, immediate source of insight, inspiration, and spiritual guidance. The external world — rivers, trees, mountains, stars — is not separate from us; it mirrors the mind and spirit, revealing the truths of the Over-Soul, the universal spirit that animates all things. Nature is both practical and symbolic. It provides for our physical needs — food, water, shelter — but every object, every phenomenon, also carries moral, spiritual, and aesthetic meaning. To perceive this meaning is a moral act; beauty and order are not trivial, but expressions of the divine, teaching harmony, proportion, and reverence. Observing nature trains the mind and soul, cultivates patience, imagination, and morality, and connects the individual to the universal laws that govern both matter and spirit. Language and thought arise from nature. Words are signs of natural facts, and through them we communicate what we learn from the world. The poet or philosopher extends these signs to convey spiritual and abstract truths, revealing the invisible through the visible. True knowledge and moral growth depend on attentive perception, self-reliance, and understanding our own nature as reflected in the world. Emerson stresses idealism: the ability to see the eternal and spiritual in the material. The simplest leaf, cloud, or rock can teach lessons about order, harmony, and power. Nature without idealism is blind; idealism without nature is empty. Union of the two allows the human soul to apprehend truth, beauty, and moral guidance. By observing and participating in nature, we align ourselves with the universal spirit and find that the temporal and the eternal, the material and the spiritual, are inseparable. Finally, Emerson celebrates the soul’s participation in the universe: growth, joy, and virtue are possible when we live in accordance with natural law. Every experience, event, and object carries instruction. By cultivating perception, imagination, and moral awareness, humans become attuned to the Over-Soul, walking through life in the company of wisdom, beauty, and power, fully alive to both the world around them and the spirit within.

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|