|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

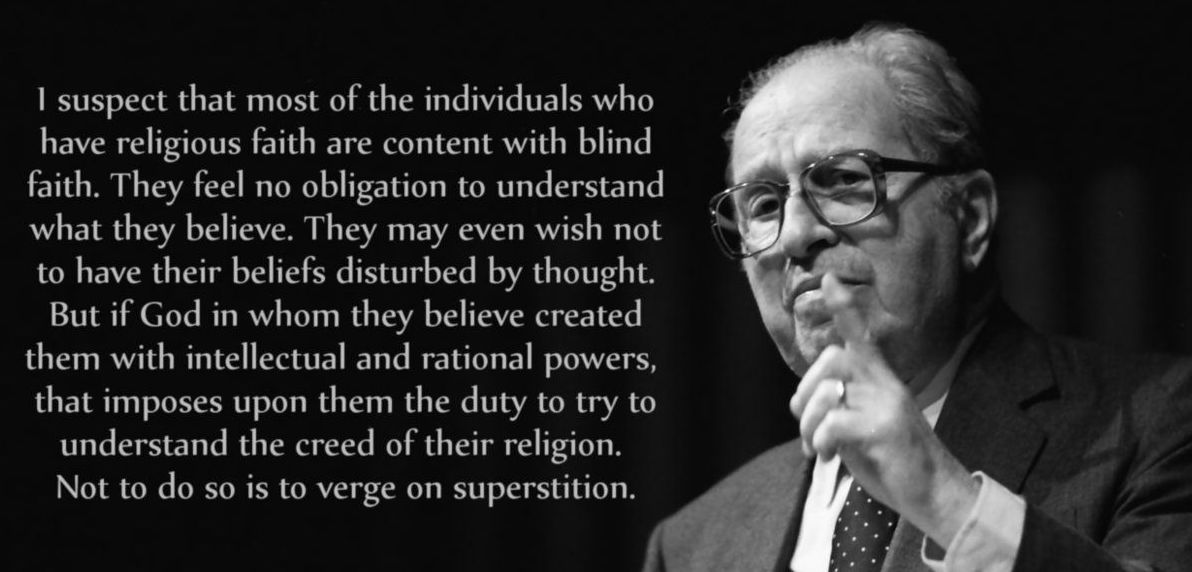

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler (1902 - 2001)

HERE, as in the chapters on GOD and MAN, almost all the great books are represented except those in mathematics and the physical sciences. Even those exceptions do not limit the sphere of love. As the theologian understands it, love is not limited to things divine and human, nor to those creatures less than man which have conscious desires. Natural love, Aquinas writes, is not only "in all the soul's powers, but also in all the parts of the body, and universally in all things: because, as Dionysius says, Beauty and goodness are beloved by all things." Love is everywhere in the universe--in all things which have their being from the bounty and generosity of God's creative love and which in return obey the law of love in seeking God or in whatever they do to magnify God's glory. Love sometimes even takes the place of other gods in the government of nature. Though he thinks the motions of the world are without direction from the gods, Lucretius opens his poem On the Nature of Things with an invocation to Venus, "the life-giver"--without whom nothing "comes forth into the bright coasts of life, nor waxes glad nor lovely." Nor is it only the poet who speaks metaphorically of love as the creative force which engenders things and renews them, or as the power which draws all things together into a unity of peace, preserving nature itself against the disruptive forces of war and hate. The imagery of love appears even in the language of science. The description of magnetic attraction and repulsion borrows some of its fundamental terms from the vocabulary of the passions; Gilbert, for example, refers to "the love of the iron for the loadstone." On the other hand, the impulsions of love are often compared with the pull of magnetism. But such metaphors or comparisons are seldom intended to conceal the ambiguity of the word "love" when it is used as a term of universal application. "Romeo wants Juliet as the filings want the magnet," writes William James, "and if no obstacles intervene he moves toward her by as straight a line as they. But Romeo and Juliet, if a wall be built between them, do not remain idiotically pressing their faces against its opposite sides"--like iron filings separated from the magnet by a card. THE LOVE BETWEEN man and woman makes all the great poems contemporaneous with each other and with ourselves. There is a sense in which each great love affair is unique--a world in itself, incomparable, unconditioned by space and time. That, at least, is the way it feels to the romantic lovers, but even to the dispassionate observer there seems to be a world of difference between the relationship of Paris and Helen in the Iliad and that of Prince Andrew and Natasha in War and Peace, or Troilus and Cressida, Tom Jones and Sophia, Don Quixote and Dulcinea, Jason and Medea, Aeneas and Dido, Othello and Desdemona, Dante and Beatrice, Hippolytus and Phaedra, Faust and Margaret, Henry V and Catherine, Paola and Francesca, Samson and Delilah, Antony and Cleopatra, Admetus and Alcestis, Orlando and Rosalind, Haemon and Antigone, Odysseus and Penelope, and Adam and Eve. The analyst can make distinctions here. He can classify these loves as the conjugal and the illicit, the normal and the perverse, the sexual and the idyllic, the infantile and the adult, the romantic and the Christian. He can, in addition, group all these loves together despite their apparent variety and set them apart from still other categories of love: the friendships between human beings without regard to gender; the familial ties--parental, filial, fraternal; the love of a man for himself, for his fellow men, for his country, for God. All these other loves are, no less than the love between man and woman, the materials of great poetry even as they are omnipresent in every human life. The friendship of Achilles and Patroclus dominates the action of the Iliad even more, perhaps, than the passion of Paris for Helen. The love of Hamlet for his father and, in another mood, for his mother overshadows his evanescent tenderness for Ophelia. Prince Hal and Falstaff, Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, Pantagruel and Panurge seem to be bound more closely by companionship than any of them is ever tied by Cupid's knot. The love of Cordelia for Lear surpasses, though it does not defeat, the lusts of Goneril and Regan. The vision of Rome effaces the image of Dido from the heart of Aeneas. Brutus lays down his life for Rome as readily as Antony gives up his life for Cleopatra. Richard III, aware that he "wants love's majesty," implies that he cannot love anyone because he is unable to love himself. Why should "I love myself," he asks, "for any good that I myself have done unto myself"? This element of self-love which, in varying degrees, prompts the actions of Achilles, Odysseus, Oedipus, Macbeth, Faust, and Captain Ahab, finds its prototype in the almost infinite amour-propre of Lucifer in Paradise Lost. This self-love, which in its extreme form the psychoanalyst calls "narcissism," competes with every other love in human life. Sometimes it qualifies these other loves; when, for example, it enters into Pierre Bezukhov's meditations about freeing his serfs and turns his sentiment of brotherly love into a piece of sentimentality which is never confirmed by action. Yet self-love, like sexual love, can be overcome by the love which is charity toward or compassion for others. True self-love, according to Locke, necessarily leads to love of neighbor; and, in Dante's view of the hierarchy of love, men ascend from loving their neighbors as themselves to loving God. Through the love he bears Virgil and Beatrice for the goodness they represent, Dante mounts to the highest heaven where he is given the Good itself to love. The panorama of human love is not confined to the great works of poetry or fiction. The same drama, with the same types of plot and character, the same lines of action, the same complications and catastrophes, appears in the great works of history and biography. The stories of love told by Herodotus, Thucydides, Plutarch, Tacitus, and Gibbon run the same gamut of the passions, the affections, the tender feeling and the sacrificial devotion, in the attachments of the great figures of history. Here the loves of a few men move the lives of many. History itself seems to turn in one direction rather than another with the turning of an emperor's heart. Historic institutions seem to draw their strength from the ardor of a single patriot's zeal; and the invincible sacrifices of the martyrs, whether to the cause of church or state, seem to perpetuate with love what neither might of arms nor skill of mind could long sustain. History's blackest as well as brightest pages tell of the lengths to which men have gone for their love's sake, and as often as not the story of the inner turbulence lies half untold between the lines which relate the consequences in acts of violence or heroism. STILL OTHER OF THE great books deal with love's exhibition of its power. A few of the early dialogues of Plato discuss love and friendship, but more of them dramatically set forth the love his disciples bear Socrates, and Socrates' love of wisdom and the truth. Montaigne can be skeptical and detached in all matters. He can suspend judgment about everything and moderate every feeling by the balance of its opposite, except in the one case of his friendship with Etienne de la Boetie where love asserts its claims above dispute and doubt. The princely examples with which Machiavelli documents his manual of worldly success are lovers of riches, fame, and power--that triad of seducers which alienates the affections of men for truth, beauty, and goodness. The whole of Pascal's meditations, insofar as they are addressed to himself, seems to express one thought, itself a feeling. "The heart has its reasons, which the reason does not know. We feel it in a thousand things. I say that the heart naturally loves the Universal Being, and also itself, according as it gives itself to them; and it hardens itself against one or the other at its will. You have rejected the one, and kept the other. Is it by reason that you love yourself?" In the Confessions of Augustine, a man who finally resolved the conflict of his loves lets his memory dwell on the torment of their disorder, in order to repent each particular sin against the love of God. "What was it that I delighted in," he writes, "but to love, and be beloved? but I kept not the measure of love, of mind to mind, friendship's bright boundary; but out of the muddy concupiscence of the flesh, and the bubblings of youth, mists fumed up which beclouded and overcast my heart, that I could not discern the clear brightness of love, from the fog of lustfulness." Augustine shows us the myriad forms of concupiscence and avarice in the lusting of the flesh and of the eyes, and in the self-love which is pride of person. In no other book except perhaps the Bible are so many loves arrayed against one another. Here, in the life of one man, as tempestuous in passion as he was strong of will, their war and peace produce his bondage and his freedom, his anguish and his serenity. In the Bible, the history of mankind itself is told in terms of love, or rather the multiplicity of loves. Every love is here--of God and Mammon, perverse and pure, the idolatry and vanity of love misplaced, every unnatural lust, every ecstasy of the spirit, every tie of friendship and fraternity, and all the hates which love engenders. THESE BOOKS of poetry and history, of meditation, confession, and revelation, teach us the facts of love even when they do not go beyond that to definition and doctrine. Before we turn to the theory of love as it is expounded by the philosophers and theologians, or to the psychological analysis of love, we may find it useful to summarize the facts of which any theory must take account. And on the level of the facts we also meet the inescapable problems which underlie the theoretical issues formed by conflicting analyses. First and foremost seems to be the fact of the plurality of loves. There are many different kinds of love--different in object, different in tendency and expression--and as they occur in the individual life, they raise the problem of unity and order. Does one love swallow up or subordinate all the others? Can more than one love rule the heart? Is there a hierarchy of loves which can harmonize all their diversity? These are the questions with which the most comprehensive theories of love find it necessary to begin. Plato's ladder of love in the Symposium has different loves for its rungs. Diotima, whom Socrates describes as his "instructress in the art of love," tells him that if a youth begins by loving a visibly beautiful form, "he will soon of himself perceive that the beauty of one form is akin to the beauty of another," and, therefore, "how foolish would he be not to recognize that the beauty in every form is one and the same." He will then "abate his violent love of the one," and will pass from being "a lover of beautiful forms" to the realization that "the beauty of the mind is more honorable than the beauty of the outward form." Thence he will be led to love "the beauty of laws and institutions . . . and after laws and institutions, he will go on to the sciences, that he may see their beauty." As Diotima summarizes it, the true order of love "begins with the beauties of earth and mounts upwards . . . from fair forms to fair practices, and from fair practices to fair notions, until from fair notions [we] arrive at the notion of absolute beauty." Aristotle classifies different kinds of love in his analysis of the types of friendship. Since the lovable consists of "the good, pleasant, or useful," he writes, "there are three kinds of friendship, equal in number to the things that are lovable; for with respect to each there is a mutual and recognized love, and those who love each other wish well to each other in that respect in which they love one another." Later in the Ethics he also considers the relation of self-love to all love of others, and asks "whether a man should love himself most, or someone else." Aquinas distinguishes between love in the sphere of the passions and love as an act of will. The former he assigns to what he calls the "concupiscible faculty" of the sensitive appetite; the latter, to the "rational or intellectual appetite." The other basic distinction which Aquinas makes is that between love as a natural tendency and as a supernatural habit. Natural love is that "whereby things seek what is suitable to them according to their nature." When love exceeds the inclinations of nature, it does so by "some habitual form superadded to the natural power," and this habit of love is the virtue of charity. Freud's theory places the origin of love in the sexual instincts, and so for him the many varieties of love are simply the forms which love takes as the libido fixes upon various objects. "The nucleus of what we mean by love," he writes, "naturally consists . . . in sexual love with sexual union as its aim. We do not separate from this," he goes on to say, "on the one hand, self-love, and on the other, love for parents and children, friendship and love for humanity in general, and also devotion to concrete objects and to abstract ideas . . . All these tendencies are an expression of the same instinctive activities." They differ from sexual love only because "they are diverted from its aim or are prevented from reaching it, though they always preserve enough of their original nature to keep their identity recognizable." Sexual love undergoes these transformations according as it is repressed or sublimated, infantile or adult in its pattern, degraded to the level of brutal sexuality or humanized by inhibitions and mixed with tenderness. All of these classifications and distinctions belong to the theory of human love. But the fact of love's diversity extends the theory of love to other creatures and to God. In the tradition of biology from Aristotle to Darwin, the mating of animals and the care of their young is thought to exhibit an emotion of love which is either sharply contrasted with or regarded as the root of human love. Darwin, for example, maintains, "it is certain that associated animals have a feeling of love for each other, which is not felt by non-social adult animals." At the opposite pole, the theologians identify God with love and see in God's love for Himself and for His creatures the principle not only of creation, and of providence and salvation, but also the measure of all other loves by which created things, and men especially, turn toward or away from God. "Beloved, let us love one another," St. John writes, "for love is of God; and everyone that loveth is born of God, and knoweth God. He that loveth not knoweth not God; for God is love. In this was manifested the love of God toward us, because that God sent his only begotten Son into the world, that we might live through him. Herein is love, not that we loved God, but that he loved us . . . And we have known and believed the love that God hath to us. God is love; and he that dwelleth in love dwelleth in God, and God in him." In the moral universe of the Divine Comedy, heaven is the realm of love, "pure light," Beatrice says, "light intellectual full of love love of true good full of joy, joy which transcends every sweetness." There courtesy prevails among the blessed, and charity alone of the theological virtues remains. The beatitude of those who see God dispenses with faith and hope, but the vision of God is inseparable from the fruition of love. "The Good which is the object of the will," Dante writes, "is all collected in it; and outside of it, that is defective which is perfect there." Desire and will are "revolved, like a wheel which is moved evenly, by the Love which moves the sun and the other stars." Hell is made by the absence of God's love--the punishment of those who on earth loved other things more than God. THERE IS A second fact about love to which poetry and history bear testimony. Love frequently turns into its opposite, hate. Sometimes there is love and hate of the same object; sometimes love inspires hate, as it occasions jealousy, of the things which threaten it. Anger and fear, too, follow in the wake of love. Love seems to be the primal passion, generating all the others according to the oppositions of pleasure and pain and by relations of cause and effect. Yet not all the analysts of love as a passion seem to agree upon this point, or at least they do not give the fact the same weight in their theories. Hobbes, for example, gives primacy to fear, and Spinoza to desire, joy, and sorrow. Spinoza defines love as "joy with the accompanying idea of an external cause," and he defines hatred similarly in terms of sorrow. Nevertheless, Spinoza, like Aquinas and Freud, deals more extensively with love and hate than with any of the other passions. He, like them, observes how their fundamental opposition runs through the whole emotional life of man. But he does not, like Aquinas, regard love as the root of all the other passions. Treating the combination of love and hate toward the same object as a mere "vacillation of the mind," he does not, like Freud, develop an elaborate theory of emotional ambivalence which tries to explain why the deepest affections of men are usually mixtures of love and hate. A THIRD FACT which appears in almost every one of the great love stories points to another aspect of love's contrariness. There seems to be no happiness more perfect than that which love confirms. But there is also no misery more profound, no depth of despair greater, than that into which lovers are plunged when they are bereft, disappointed, unrequited. These questions paraphrase the soliloquies of lovers in the great tragedies and comedies of love. For every praise of love there is, in Shakespearian speech or sonnet, an answering complaint. "All creatures in the world through love exist, and lacking love, lack all that may persist." But "thou blind fool, love, what does thou to mine eyes, that they behold and see not what they see?" "The greater castle of the world is lost," says Antony to Cleopatra; "we have kissed away kingdoms and provinces." But in Romeo's words to Juliet, "My bounty is as boundless as the sea, my love as deep; the more I give to thee, the more I have, for both are infinite." Love is all opposites--the only reality, the great illusion; the giver of life and its consumer; the benign goddess whose benefactions men beseech, and-to such as Hippolytus or Didothe dread Cyprian who wreaks havoc and devastation. She is a divinity to be feared when not propitiated, her potions are poison, her darts are shafts of destruction. Love is itself an object of love and hate. Men fall in love with love and fight against it. Omnia vincit amor, Virgil writes -- "love conquers all." In the dispassionate language of the moralist, the question is simply whether love is good or bad, a component of happiness or an obstacle thereto. How the question is answered depends upon the kind of love in question. The love which consists in the best type of friendship seems indispensable to the happy life and, more than that, to the fabric of any society, domestic or political. Such love, Aristotle writes, "is a virtue or implies virtue, and is besides most necessary with a view to living. For without friends no one would choose to live though he had all other goods .... Friendship seems too to hold states together, and lawgivers care more for it than for justice." When it is founded on virtue, it goes further than justice, for it binds men together through benevolence and generosity. "When men are friends," Aristotle says, "they have no need of justice." But Aristotle does not forget that there are other types of friendship, based on utility or pleasure-seeking rather than upon the mutual admiration of virtuous men. Here, as in the case of other passions, the love may be good or bad. It is virtuous only when it is moderated by reason and restrained from violating the true order of goods, in conformity to which man's various loves should themselves be ordered. When the love in question is the passion of the sexual instinct, some moralists think that temperance is an inadequate restraint. Neither reason nor law is adequate to the task of subduing -- or, as Freud would say, of domesticating -- the beast. To the question Socrates asks, whether life is harder towards the end, the old man Cephalus replies in the words of Sophocles, when he was asked how love suits with age, "I feel as if I had escaped from a mad and furious master." In the most passionate diatribe against love's passion, Lucretius condemns the sensual pleasures which are so embittered with pain. Venus should be entirely shunned, for once her darts have wounded men,"the sore gains strength and festers by feeding, and day by day the madness grows, and the misery becomes heavier .... This is the one thing, whereof the more and more we have, the more does our heart burn with the cursed desire .... When the gathering desire is sated, the old frenzy is back upon them . . .nor can they discover what device may conquer their disease; in such deep doubt they waste beneath their secret wound . . .These ills are found in love that is true and fully prosperous; but when love is crossed and hopeless, there are ills which you might detect with closed eyes, ills without number; so that it is better to be on the watch beforehand, even as I have taught you, and to beware that you are not entrapped. For to avoid being drawn into the meshes of love, is not so hard a task as when caught amid the toils to issue out and break through the strong bonds of Venus." In the doctrines of most moralists, however, the sexual passion calls for no special treatment different from other appetites and passions. Because it is more complex in its manifestations, perhaps, and more imperious in its urges, more effort on the part of reason maybe required to regulate it, to direct or restrain it. Yet no special principles of virtue or duty apply to sexual love. Even the religious vow of chastity is matched by the vow of poverty. The love of money is as serious a deflection from loving God as the lust of the flesh. WHAT IS COMMON to all these matters is discussed in the chapters on DUTY, EMOTION, VIRTUE, and SIN. But here one more fact remains to be considered--the last fact about love which the poets and the historians seem to lay before the moralists and theologians. When greed violates the precepts of justice, or gluttony those of temperance, the vice or sin appears to have no redeeming features. These are weaknesses of character incompatible with heroic stature. But many of the great heroes of literature are otherwise noble men or women who have, for love's sake, deserted their duty or transgressed the rules of God and man, acknowledging their claims and yet choosing to risk the condemnation of society even to the point of banishment, or to put their immortal souls in peril. The fact seems to be that only love retains some honor when it defies morality; not that moralists excuse the illicit act, but that in the opinion of mankind, as evidenced by its poetry at least, love has some privileged status. Its waywardness and even its madness are extenuated. The poets suggest the reason for this. Unlike the other passions which man shares with the animals, characteristically human love is a thing of the spirit as well as the body. A man is piggish when he is a glutton, a jackal when he is craven, but when his emotional excess in the sphere of love lifts him to acts of devotion and sacrifice, he is incomparably human. That is why the great lovers, as the poets depict them, seem admirable in spite of their transgressions. They almost seem to be justified poetically, at least, if not morally - in acting as if love exempted them from ordinary laws; as if their love could be a law unto itself. "Who shall give a lover any law?" Arcite asks in Chaucer's Knight's Tale. "Love is a greater law," he says, "than man has ever given to earthly man." To a psychologist like Freud, the conflict between the erotic impulses and morality is the central conflict in the psychic life of the individual and between the individual and society. There seems to be no happy resolution unless each is somehow accommodated to the other. At one extreme of repression, "the claims of our civilization," according to Freud, "make life too hard for the greater part of humanity, and so further the aversion to reality and the origin of neuroses"; the individual suffers neurotic disorders which result from the failure of the repressed energies to find outlets acceptable to the moral censor. At the other extreme of expression, the erotic instinct "would break all bounds and the laboriously erected structure of civilization would be swept away." Integration would seem to be achieved in the individual personality and society would seem to prosper only when sexuality is transformed into those types of love which reinforce laws and ii duties with emotional loyalty to moral ideals and invest ideal objects with their energies, creating the highest goods of civilization. To the theologian, the conflict between love and morality remains insoluble--not in principle, but in practice--until love itself supplants all other rules of conduct. The "good man," according to Augustine, is not he "who knows what is good, but who loves it. Is it not then obvious," he goes on to say, "that we love in ourselves the very love wherewith we love whatever we love? For there is also a love wherewith we love that which we ought not to love; and this love is hated by him who loves that wherewith he loves what ought to be loved, For it is quite possible for both to exist in one man. And this co-existence is good for a man, to the end that this love which conduces to our living well may grow, and the other, which leads us to evil may decrease, until our whole life be perfectly healed and transmuted into good." Only a better love, a love that is wholly virtuous and right, has the power requisite to overcome love's errors. With this perfect love goes only one rule, Augustine says: Dilige, et quod vis fac -- love, and do what you will. This perfect love, which alone deserves to be a law unto itself, is more than fallen human nature can come by without God's grace. It is, according to Christian theology, the supernatural virtue of charity whereby men participate in God's love of Himself and His creatures--loving God with their whole heart and soul and mind, and their neighbors as themselves. On these two precepts of charity, according to the teaching of Christ, "depends the whole law and the prophets." The questions which Aquinas considers in his treatise on charity indicate that the theological resolution of the conflict between love and morality is, in essence, the resolution of a conflict between diverse loves, a resolution accomplished by the perfection of love itself. Concerning the objects and order of charity, he asks, for example, "whether we should love charity out of charity," "whether irrational creatures also ought to be loved out of charity," "whether a man ought to love his body out of charity," "whether we ought to love sinners out of charity," "whether charity requires that we should love our enemies," "whether God ought to be loved more than our neighbors," "whether, out of charity, man is bound to love God more than himself," "whether, out of charity, man ought to love himself more than his neighbor," "whether a man ought to love his neighbor more than his own body," "whether we ought to love one neighbor more than another," "whether we ought to love those who are better more than those who are more closely united to us," "whether a man ought, out of charity, to love his children more than his father," "whether a man ought to love his wife more than his father and mother," "whether a man ought to love his benefactor more than one he has benefited." THE DIVERSITY of love seems to be both the basic fact and the basic problem for the psychologist, the moralist, the theologian. The ancient languages have three distinct words for the main types of love: eros, philia, agape in Greek; amor, amicitia (or dilectio), and caritas in Latin. Because English has no such distinct words, it seems necessary to use such phrases as "sexual love," "love of friendship," and "love of charity" in order to indicate plainly that love is common to all three, and to distinguish the three meanings. Yet we must observe what Augustine points out, namely, that the Scriptures "make no distinction between amor, dilectio, and caritas," and that in the Bible "amor is used in a good connection." The problem of the kinds of love seems further to be complicated by the need to differentiate and relate love and desire. Some writers use the words "love" and "desire" interchangeably, as does Lucretius who, in speaking of the pleasures of Venus, says that "Cupid [i.e., desire] is the Latin name of love." Some, like Spinoza, use the word "desire" as the more general word and "love" to name a special mode of desire. Still others use "love" as the more general word and "desire" to signify an aspect of love. "Love," Aquinas writes, "is naturally the first act of the will and appetite; for which reason all the other appetitive movements presuppose love, as their root and origin. For nobody desires anything nor rejoices in anything, except as a good that is loved." One thing seems to be clear, namely, that both love and desire belong to the appetitive faculty--to the sphere of the emotions and the will rather than to the sphere of perception and knowledge. When a distinction is made between desire and love as two states of appetite, it seems to be based on their difference in tendency. As indicated in the chapter of DESIRE, the tendency of desire is acquisitive. The object of desire is a good to be possessed, and the drive of desire continues until, with possession, it is satisfied. Love equated with desire does not differ from any other hunger. But there seems to be another tendency which impels one not to possess the object loved, but to benefit it. The lover wishes the well-being of the beloved, and reflexively wishes himself well through being united with the object of his love. Where desire devoid of love is selfish in the sense of one's seeking goods or pleasures for oneself without any regard for the good of the other, be it thing or person, love seeks to give rather than to get, or to get only as the result of giving. Whereas nothing short of physical possession satisfies desire, love can be satisfied in the contemplation of its object's beauty or goodness. It has more affinity with knowledge than with action, though it goes beyond knowledge in its wish to act for the good of the beloved, as well as in its wish to be loved in return. Those who distinguish love and desire in such terms usually repeat the distinction in differentiating kinds of love. The difference between sexual love and the love which is pure friendship, for example, is said to rest on the predominance of selfish desires in the one and the predominance of altruistic motives in the other. Sexual love is sometimes called the "love of desire" to signify that it is a love born of desire; whereas in friendship love is thought to precede desire and to determine its wishes. In contrast to the love of desire, the love of friendship makes few demands. "In true friendship, wherein I am perfect," Montaigne declares, "I more give myself to my friend, than I endeavor to attract him to me. I am not only better pleased in doing him service than if he conferred a benefit upon me, but, moreover, had rather he should do himself good than me, and he most obliges me when he does so; and if absence be either more pleasant or convenient for him, 'tis also more acceptable to me than his presence." These two loves appear in most of the great analyses of love, though under different names: concupiscent love and fraternal love; the friendship base on pleasure or utility and the friendship based on virtue; animal and human love; sexuality and tenderness. Sometimes they are assigned to different faculties: the love of desire to the sensitive appetite or the sphere of instinct and emotion; the love of friendship to the will or faculty of intellectual desire, capable of what Spinoza calls the amor intellectualis Dei -- "the intellectual love of God." Sometimes the two kinds of love are thought able to exist in complete separation from one another as well as in varying degrees of mixture, as in romantic and conjugal love; and sometimes the erotic or sexual component is thought to be present to some degree in all love. Though he asserts this, Freud does not hold the converse, that sexuality is always accompanied by the tenderness which characterizes human love. The opposite positions here seem to be correlated with opposed views of the relation of man to other animals, or with opposed theories of human nature, especially in regard to the relation of instinct and reason, the senses and the intellect, the emotions and the will. As suggested above, romantic love is usually conceived as involving both possessive and altruistic motives, the latter magnified by what its critics regard as an exaggerated idealization of the beloved. The theological virtue of charity, on the other hand, is purely a love of friendship, its purity made perfect by its supernatural foundation. One of the great issues here is whether the romantic is compatible with the Christian conception of love, whether the adoration accorded a beloved human being does not amount to deification--as much a violation of the precepts of charity as the pride of unbounded self-love. Which view is taken affects the conception of conjugal love and the relation of love in courtship to love in marriage. These matters and, in general, the forms of love in the domestic community are discussed in the chapter on FAMILY.

|

||

|

|