|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

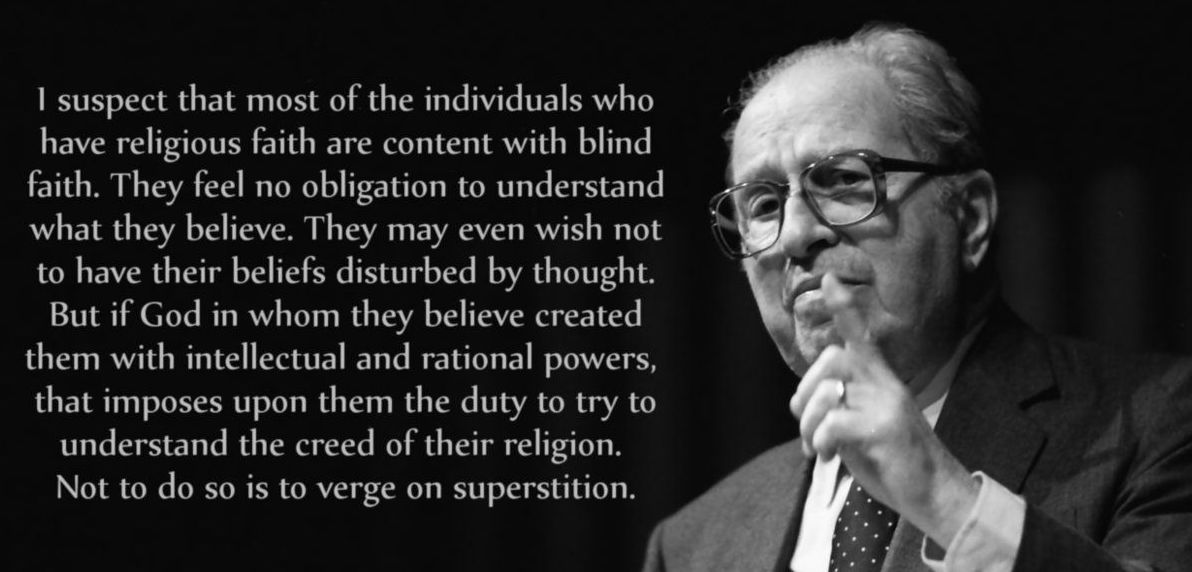

Philosopher Mortimer J. Adler (1902 - 2001)

THE emotions claim our attention in two ways. We experience them, sometimes in a manner which overwhelms us; and we analyze them by defining and classifying the several passions, and by studying their role in human life and society. We seldom do both at once, for analysis requires emotional detachment, and moments of passion do not permit study or reflection. With regard to the emotions the great books are similarly divided into two sorts--those which are theoretical discussions and those which concretely describe the passions of particular men, exhibit their vigor, and induce in us a vicarious experience. Books of the first sort are scientific, philosophical, or theological treatises. Books of the second sort are the great epic and dramatic poems, the novels and plays, the literature of biography and history. We customarily think of the emotions as belonging to the subject matter of psychology -- proper to the science of animal and human behavior. It is worth noting therefore that this is largely a recent development, which appears in the works of Darwin, James, and Freud. In earlier centuries, the analysis of the passions occurs in other contexts: in treatments of rhetoric, as in certain dialogues of Plato and in Aristotle's Rhetoric; in the Greek discussions of virtue and vice; in the moral theology of Aquinas and in Spinoza's Ethics; and in books of political theory, such as Machiavelli's Prince and Hobbes' Leviathan. Descartes' treatise on The Passions of the Soul is probably one of the first discourses on the subject to be separated from the practical considerations of oratory, morals, and politics. Only subsequently do the emotions become an object of purely theoretic interest in psychology. But even then the interest of the psychiatrist or psychoanalyst--to the extent that it is medical or therapeutic--has a strong practical bent. In the great works of poetry and history no similar shift takes place as one goes from Homer and Virgil to Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, from Greek to Shakespearean tragedy, from Plutarch and Tacitus to Gibbon. What Wordsworth said of the lyric poem--that it is "emotion recollected in tranquillity"--may not apply to the narratives in an identical sense. This is no less true of historical narrative than of fiction. The memorable actions of men on the stage of history did not occur in calm and quiet. It is impossible, of course, to cite all the relevant passages of poetry and history. In many instances, nothing less than a whole book would suffice. The particular references given in this chapter, which are far from exhaustive, have been selected for their peculiar exemplary significance in relation to a particular topic; but for the whole range of topics connected with emotion, the reader should certainly seek further in the realms of history and poetry for the raw materials which the scientists and philosophers have tried to analyze and understand. To the student of the emotions, Bacon recommends "the poets and writers of histories" as "the best doctors of this knowledge; where we may find painted forth with great life, how affections are kindled and incited; and how pacified and refrained; and how again contained from act and further degree; how they disclose themselves; how they work; how they vary; how they gather and fortify; how they are enwrapped one within another; and how they do fight and encounter one with another; and other like particularities." FOUR WORDS -- "passion," "affection" or "affect," and "emotion" -- have been traditionally used to designate the same psychological fact. Of these, "affection" and "affect" have ceased to be generally current, although we do find them in Freud; and "passion" is now usually restricted to mean one of the emotions, or the more violent aspect of any emotional experience. But if we are to connect discussions collected from widely separated centuries, we must be able to use all these words interchangeably. The psychological fact to which they all refer is one every human being has experienced in moments of great excitement, especially during intense seizure by rage or fear. In his treatise On the Circulation of the Blood, Harvey calls attention to "the fact that in almost every affection, appetite, hope, or fear, our body suffers, the countenance changes, and the blood appears to course hither and thither. In anger the eyes are fiery and the pupils contracted; in modesty the cheeks are suffused with blushes; in fear, and under a sense of infamy and of shame, the face is pale" and "in lust how quickly is the member distended with blood and erected!" Emotional experience seems to involve an awareness of widespread bodily commotion, which includes changes in the tension of the blood vessels and the muscles, changes in heartbeat and breathing, changes in the condition of the skin and other tissues. Though some degree of bodily disturbance would seem to be an essential ingredient in all emotional experience, the intensity and extent of the physiological reverberation, or bodily commotion, is not the same or equal in all the emotions. Some emotions are much more violent than others. This leads William James to distinguish what he calls the "coarser emotions ... in which every one recognizes a strong organic reverberation" from the "subtler emotions" in which the "organic reverberation is less obvious and strong." This fact is sometimes used to draw the line between what are truly emotions and what are only mild feelings of pleasure and pain or enduring sentiments. Nevertheless, sentiments may be emotional residues--stable attitudes which pervade a life even during moments of emotional detachment and calm--and pleasure and pain may color all the emotions. "Pleasure and pain," Locke suggests, are "the hinges on which our passions turn." Even though they may not be passions in the strict sense, they are obviously closely connected with them. THAT THE EMOTIONS are organic disturbances, upsetting the normal course of the body's functioning, is sometimes thought to be a modern discovery, connected with the James-Lange theory that the emotional experience is nothing but the "feeling of . . . the bodily changes" which "follow directly the perception of the exciting fact." On this view, the explanation of emotion seems to be the very opposite of "common sense," which says, "we meet a bear, are frightened, and run." According to James, "this order of sequence is incorrect," and "the more rational statement is that we feel ... afraid because we tremble." In other words, we do not run away because we are afraid, but are afraid because we run away. This fact about the emotions was known to antiquity and the Middle Ages. Aristotle, for example, holds that mere awareness of an object does not induce flight unless "the heart is moved," and Aquinas declares that "passion is properly to be found where there is corporeal transmutation." He describes at some length the bodily changes which take place in anger and fear. Only very recently, however, have apparatus and techniques been devised for recording and, in some cases, measuring the physiological changes accompanying experimentally produced emotions--in both animals and men. Modern theory also tries to throw some light on these organic changes by pointing out their adaptive utility in the struggle for existence. This type of explanation is advanced by Darwin in The Expression of Emotions in Man and Animals, and is adopted by other evolutionists. "The snarl or sneer, the one-sided uncovering of the upper teeth," James writes, "is accounted for by Darwin as a survival from the time when our ancestors had large canines, and unfleshed them (as dogs now do) for attack ... The distention of the nostrils in anger is interpreted by Spencer as an echo of the way in which our ancestors had to breathe when, during combat, their 'mouth was filled up by a part of the antagonist's body that had been seized' . . . The redding of the face and neck is called by Wundt a compensatory arrangement for relieving the brain of the blood-pressure which the simultaneous excitement of the heart brings with it. The effusion of tears is explained both by this author and by Darwin to be a blood-withdrawing agency of a similar sort." Reviewing statements of this sort, James is willing to concede that "some movements of expression can be accounted for as weakened repetitions of movements which formerly (when they were stronger) were of utility to the subject"; but though we may thus "see the reason for a few emotional reactions," he thinks "others remain for which no plausible reason can even be conceived." The latter, James suggests, "may be reactions which are purely mechanical results of the way in which our nervous centres are framed, reactions which, although permanent in us now, may be called accidental as far as their origin goes." Whether or not all the bodily changes which occur in such emotions as anger or fear serve the purpose of increasing the animal's efficiency in combat or flight--as, for example, the increase of sugar in the blood and the greater supply of blood to arms and legs seem to do--the basic emotions are generally thought to be connected with the instinctively determined patterns of behavior by which animals struggle to survive. "The actions we call instinctive," James writes, "are expressions or manifestations of the emotions"; or, as other writers suggest, an emotion, whether in outward expression or in inner experience, is the central phase of an instinct in operation. The observation of the close relation between instinct and emotion does not belong exclusively to modern, or post-Darwinian, thought. The ancients also recognize it, though in different terms. Following Aristotle's analysis of the various "interior senses," Aquinas, for example, speaks of the "estimative power" by which animals seem to be innately prepared to react to things useful or harmful. "If an animal were moved by pleasing and disagreeable things only as affecting the sense" -- that is, the exterior senses -- "there would be no need to suppose," Aquinas writes, "that an animal has a power besides the apprehension of those forms which the senses perceive, and in which the animal takes pleasure, or from which it shrinks with horror." But animals need to seek or avoid certain things on account of their advantages or disadvantages, and such emotional reactions of approach or avoidance require, in his opinion, a sense of the useful and the dangerous, which is innate rather than learned. The estimative power thus seems to play a role which later writers assign to instinct. The relation of instinct to the emotions and to fundamental biological needs is further considered from other points of view, in the chapter on DESIRE and HABIT. LIKE DESIRE, emotion is neither knowledge nor action, but something intermediate between the one and the other. The various passions are usually aroused by objects perceived, imagined, or remembered, and once aroused they in turn originate impulses to act in certain ways. For example, fear arises with the perception of a threatening danger or with the imagination of some fancied peril. The thing feared is somehow recognized as capable of inflicting injury with consequent pain. The thing feared is also something from which one naturally tends to flee in order to avoid harm. Once the danger is known and until it is avoided by flight or in some other way, the characteristic feeling of fear pervades the whole experience. It is partly a result of what is known and what is done, and partly the cause of how things seem and how one behaves. Analytically isolated from its causes and effects, the emotion itself seems to be the feeling rather than the knowing or the doing. But it is not simply an awareness of a certain bodily condition. It also involves the felt impulse to do something about the object of the passion. Those writers who, like Aquinas, identify emotion with the impulse by which "the soul is drawn to a thing," define the several passions as specifically different acts of appetite or desire-specific tendencies to action. Aquinas, for instance, adopts the definition given by Damascene: "Passion is a movement of the sensitive appetite when we imagine good or evil." Other writers who, like Spinoza, find that "the order of the actions and passions of our body is coincident in nature with the order of the actions and passions of the mind," stress the cognitive rather than the impulsive aspect of emotion. They accordingly define the passions in terms of the characteristic feelings, pleasant and unpleasant, which flow from the estimation of certain objects as beneficial or harmful. Spinoza goes furthest in this direction when he says that "an affect or passion of the mind is a confused idea . . . by which the mind arms of its body, or any part of it, a greater or less power of existence than before." There seems to be no serious issue here, for writers of both sorts acknowledge, though with different emphasis, the two sides of an emotion -- the cognitive and the impulsive, that which faces toward the object and that which leads into action. On either view, the human passions are regarded as part of man's animal nature. It is generally admitted that disembodied spirits, if such exist, cannot have emotions. The angels, Augustine writes, "feel no anger while they punish those whom the eternal law of God consigns to punishment, no fellow-feeling with misery while they relieve the miserable, no fear while they aid those who are in danger." When we do ascribe emotions to spirits, it is, Augustine claims, because, "though they have none of our weakness, their acts resemble the actions to which these emotions move us." In connection with the objects which arouse them, the emotions necessarily depend upon the senses and the imagination; and their perturbations and impulses require bodily organs for expression. That is why, as indicated in the chapter on DESIRE, some writers separate the passions from acts of the will, as belonging to the sensitive or animal appetite rather than to the rational or specifically human appetite. Even those writers who do not place so high an estimate on the role of reason, refer the emotions to the animal aspect of human behavior, or to what is sometimes called "man's lower nature." When this phrase is used, it usually signifies the passions as opposed to the reason, not the purely vegetative functions which man shares with plants as well as animals. There seems to be no doubt that emotions are common to men and animals and that they are more closely related to instinct than to reason or intelligence. Darwin presents many instances which, he claims, prove that "the senses and intuitions, the various emotions and faculties, such as love, memory, attention, curiosity, imitation, reason, etc., of which man boasts, may be found in an incipient, or even sometimes in a well-developed, condition in the lower animals." Where Darwin remarks upon "the fewness and the comparative simplicity of the instincts in the higher animals . . . in contrast with those of the lower animals," James takes the position that man "is the animal richest in instinctive impulses." However that issue is decided, the emotions seem to be more elaborately developed in the higher animals, and man's emotional life would seem to be the most complex and varied of all. The question then arises whether particular passions are identical--or are only analogous -- when they occur in men and animals. For example, is human anger, no matter how closely it resembles brute rage in its physiology and impulses, nevertheless peculiarly human? Do men alone experience righteous indignation because of some admixture in them of reason and passion? When similar questions are asked about the sexual passions of men and animals, the answers will determine the view one takes of the characteristically human aspects of love and hate. It may even be asked whether hate, as men suffer it, is ever experienced by brutes, or whether certain passions, such as hope and despair, are known to brutes at all? IN THE TRADITIONAL theory of the emotions, the chief problem, after the definition of emotion, is the classification or grouping of the passions, and the ordering of particular passions. The vocabulary of common speech in all ages and cultures includes a large number of words for naming emotions, and it has been the task of analysts to decide which of these words designate distinct affects or affections. The precise character of the object and the direction of the impulse have been, for the most part, the criteria of definition. As previously noted, it is but recently that the experimental observation of bodily changes has contributed to the differentiation of emotions from one another. Spinoza offers the longest listing of the passions. For him, the emotions, which are all "compounded of the three primary affects, desire, joy, and sorrow," develop into the following forms: astonishment, contempt, love, hatred, inclination, aversion, devotion, derision, hope, fear, confidence, despair, gladness, remorse, commiseration, favor, indignation, overestimation, envy, compassion, self-satisfaction, humility, repentance, pride, despondency, self-exaltation, shame, regret, emulation, gratitude, benevolence, anger, vengeance, ferocity, audacity, consternation, courtesy, ambition, luxuriousness, drunkenness, avarice, lust. Many of the foregoing are, for Hobbes, derived from what he calls "the simple passions," which include "appetite, desire, love, aversion, hate, joy, and grief." There are more emotions in Spinoza's list than either Aristotle or Locke or James mentions, but none which they include is omitted. Some of the items in Spinoza's enumeration are treated by other writers as virtues and vices rather than as passions. The passions have been classified by reference to various criteria. As we have seen, James distinguishes emotions as "coarse" or "subtle" in terms of the violence or mildness of the accompanying physiological changes; and Spinoza distinguishes them according as "the mind passes to a greater perfection" or "to a less perfection." Spinoza's division would also seem to imply a distinction between the beneficial and the harmful in the objects causing these two types of emotion, or at least to involve the opposite components of pleasure and pain, for in his view the emotions which correspond to "a greater or less power of existence than before" are attended in the one case by "pleasurable excitement" and in the other by "pain." Hobbes uses another principle of division. The passions differ basically according to the direction of their impulses-according as each is "a motion or endeavor . . . to or from the object moving." Aquinas adds still another criterion--"the difficulty or struggle . . . in acquiring certain goods or in avoiding certain evils" which, in contrast to those we "can easily acquire or avoid," makes them, therefore, "of an arduous or difficult nature." In these terms, he divides all the passions into the "concupiscible," which regard "good or evil simply" (i.e., love, hate, desire, aversion, joy, sorrow), and the "irascible," which "regard good or evil as arduous through being difficult to obtain or avoid" (i.e., fear, daring, hope, despair, anger). Within each of these groups, Aquinas pairs particular passions as opposites, such as joy and sorrow, or hope and despair, either according to the "contrariety of object, i.e., of good and evil . . . or according to approach and withdrawal." Anger seems to be the only passion for which no opposite can be given, other than that "cessation from its movement" which Aristotle calls "calmness" and which Aquinas says is an opposite not by way of "contrariety but of negation or privation." Using these distinctions, Aquinas also describes the order in which one passion leads to or generates another, beginning with love and hate, passing through hope, desire, and fear, with their opposites, and, after anger, ending in joy or despair. On one point, all observers and theorists from Plato to Freud seem to agree, namely, that love and hate lie at the root of all the other passions and generate hope or despair, fear and anger, according as the aspirations of love prosper or fail. Nor is the insight that even hate derives from love peculiarly modern, though Freud's theory of what he calls the "ambivalence" of love and hate toward the same object, seems to be part of his own special contribution to our understanding of the passions. THE ROLE OF THE emotions or passions in human behavior has always raised two questions, one concerning the effect of conflict between diverse emotions, the other concerning the conflict between the passions and the reason or will. It is the latter question which has been of the greatest interest to moralists and statesmen. Even though human emotions may have instinctive origin and be innately determined, man's emotional responses seem to be subject to voluntary control, so that men are able to form or change their emotional habits. If this were not so, there could be no moral problem of the regulation of the passions; nor, for that matter, could there be a medical problem of therapy for emotional disorders. The psychoanalytic treatment of neuroses seems, moreover, to assume the possibility of a voluntary, or even a rational, resolution of emotional conflicts--not perhaps without the aid of therapeutic efforts to uncover the sources of conflict and to remove the barriers between repressed emotion and rational decision. The relation of the passions to the will, especially their antagonism, is relevant to the question whether the actions of men always conform to their judgments of good and evil, or right and wrong. As Socrates discusses the problem of knowledge and virtue, it would seem to be his view that a man who knows what is good for him will act accordingly. Men may "desire things which they imagine to be good," he says, "but which in reality are evil." Hence their misconduct will be due to a mistaken judgment, not to a discrepancy between action and thought. Eliminating the case of erroneous judgment, Socrates gets Meno to admit that "no man wills or chooses anything evil." Aristotle criticizes the Socratic position which he summarizes in the statement that "no one . . . when he judges acts against what he judges best--people act badly only by reason of ignorance." According to Aristotle, "this view plainly contradicts the observed facts." Yet he admits that whatever a man does must at least seem good to him at the moment; and to that extent the judgment that something is good or bad would seem to determine action accordingly. In his analysis of incontinence, Aristotle tries to explain how a man may act against what is his better judgment and yet, at the moment of action, seek what he holds to be good. Action may be caused either by a rational judgment concerning what is good or by an emotional estimate of the desirable. If these two factors are independent of one another--more than that, if they can tend in opposite directions--then a man may act under emotional persuasion at one moment in a manner contrary to his rational predilection at another. That a man may act either emotionally or rationally, Aristotle thinks, explains how, under strong emotional influences, a man can do the very opposite of what his reason would tell him is right or good. The point is that, while the emotions dominate his mind and action, he does not listen to reason. These matters are further discussed in the chapter on TEMPERANCE. But it should be noted here that the passions and the reason, or the "lower" and the "higher" natures of man, are not always in conflict. Sometimes emotions or emotional attitudes serve reason by supporting voluntary decisions. They reinforce and make effective moral resolutions which might otherwise be too difficult to execute. THE ANCIENTS DID not underestimate the force of the passions, nor were they too confident of the strength of reason in its struggle to control them, or to be free of them. They were acquainted with the violence of emotional excess which they called "madness" or "frenzy." So, too, were the theologians of the Middle Ages and modern philosophers like Spinoza and Hobbes. But not until Freud--and perhaps also William James, though to a lesser extent--do we find in the tradition of the great books insight into the pathology of the passions, the origin of emotional disorders, and the general theory of the neuroses and neurotic character as the consequence of emotional repression. For Freud, the primary fact is not the conflict between reason and emotion, or, in his language, between the ego and the id. It is rather the repression which results from such conflict. On the one side is the ego, which "stands for reason and circumspection" and has "the task of representing the external world, or expressing what Freud calls "the reality-principle." Associated with the ego is the superego--"the vehicle of the ego-ideal, by which the ego measures itself, towards which it strives, and whose demands for ever-increasing perfection it is always striving to fulfill." On the other side is the id, which "stands for the untamed passions" and is the source of instinctual life. The ego, according to Freud, is constantly attempting "to mediate between the id and reality" and to measure up to the ideal set by the super-ego, so as to dethrone "the pleasure-principle, which exerts undisputed sway over the processes in the id, and substitute for it the reality-principle, which promises greater security and greater success." But sometimes it fails in this task. Sometimes, when no socially acceptable channels of behavior are available for expressing emotional drives in action, the ego, supported by the super-ego, represses the emotional or instinctual impulses, that is, prevents them from expressing themselves overtly. Freud's great insight is that emotions repressed do not atrophy and disappear. On the contrary, their dammed-up energies accumulate and, like a sore, they fester inwardly. Together with related ideas, memories, and wishes, the repressed emotions form what Freud calls a "complex," which is not only the active nucleus of emotional disorder, but also the cause of neurotic symptoms and behavior-phobias and anxieties, obsessions or compulsions, and the various physical manifestations of hysteria, such as a blindness or a paralysis that has no organic basis. The line between the neurotic and the normal is shadowy, for repressed emotional complexes are, according to Freud, also responsible for the hidden or latent psychological significance of slips of speech, forgetting, the content of dreams, occupational or marital choices, and a wide variety of other phenomena usually regarded as accidental or as rationally determined. In fact, Freud sometimes goes to the extreme of insisting that all apparently rational processes--both of thought and decision--are themselves emotionally determined; and that most, or all, reasoning is nothing but the rationalization of emotionally fixed prejudices or beliefs. "The ego," he writes, "is after all only a part of the id, a part purposively modified by its proximity to the dangers of reality." The ancient distinction between knowledge and opinion seems to be in essential agreement with the insight that emotions can control the course of thinking. But at the same time it denies that all thinking is necessarily dominated by the passions. The sort of thinking which is free from emotional bias or domination may result in knowledge, if reason itself is not defective in its processes. But the sort of thinking which is directed and determined by the passions must result in opinion. The former is reasoning; the latter what Freud calls "rationalization" or sometimes "wishful thinking." BECAUSE THEY CAN be ordered when they get out of order, the emotions raise problems for both medicine and morals. Whether or not there is a fundamental opposition between the medical and the moral approaches to the problem, whether psychotherapy is needed only when morality has failed, whether morality is itself partly responsible for the disorders which psychotherapy must cure, the difference between the medical and the moral approaches is clear. Medically, emotional disorders call for diagnosis and therapy. Morally, they call for criticism and correction. Human bondage, according to Spinoza, consists in "the impotence of man to govern or restrain the affects . . . for a man who is under their control is not his own master." A free man he describes as one "who lives according to the dictates of reason alone," and he tries to show "how much reason itself can control the affects" to achieve what he calls "freedom of mind or blessedness." While moralists tend to agree on this point, they do not all offer the same prescription for establishing the right relation between man's higher and lower natures. The issue which arises here is also discussed in the chapters on DESIRE and DUTY. It exists between those who think that the passions are intrinsically evil, the natural enemies of a good will, lawless elements always in rebellion against duty; and those who think that the passions represent a natural desire for certain goods which belong to the happy life, or a natural aversion for certain evils. Those who, like the Stoics and Kant, tend to adopt the former view recommend a policy of attrition toward the passions. Their force must be attenuated in order to emancipate reason from their influence and to protect the will from their seductions. Nothing is lost, according to this theory, if the passions atrophy and die. But if, according to the opposite doctrine, the passions have a natural place in the moral life, then the aim should be, not to dispossess them entirely, but to keep them in their place. Aristotle therefore recommends a policy of moderation. The passions can be made to serve reason's purposes by restraining them from excesses and by directing their energies to ends which reason approves. As Aristotle conceives them, certain of the virtues--especially temperance and courage--are stable emotional attitudes, or habits of emotional response, which conform to reason and carry out its rule. The moral virtues require more than a momentary control or moderation of the passions; they require a discipline of them which has become habitual. What Aristotle calls continence, as opposed to virtue, consists in reason's effort to check emotions which are still unruly because they have not yet become habituated to reason's rule. The fact of individual differences in temperament is of the utmost importance to the moralist who is willing to recognize that universal moral rules apply to individuals differently according to their temperaments. Both psychologists and moralists have classified men into temperamental types by reference to the dominance or deficiency of certain emotional predispositions in their inherited makeup. These temperamental differences also have a medical or physiological aspect insofar as certain elements in human physique--the four bodily humors of the ancients or the hormones of modern endocrinology--seem to be correlated with types of personality. ONE OF THE GREAT issues in political theory concerns the role of the passions in human association. Have men banded together to form states because they feared the insecurity and the hazards of natural anarchy and universal war, or because they sought the benefits which only political life could provide? In the political community, once it is formed, do love and friendship or distrust and fear determine the relation of fellow citizens, or of rulers and ruled ? Should the prince, or any other man who wishes to get and hold political power, try to inspire love or to instill fear in those whom he seeks to dominate? Or are each of these emotions useful for different political purposes and in the handling of different kinds of men? Considering whether for the success of the prince it is "better to be loved than feared or feared than loved," Machiavelli says that "one should wish to be both, but, because it is difficult to unite them in one person, it is much safer to be feared than loved, when, of the two, either must be dispensed with . . . . Nevertheless," he continues, "a prince ought to inspire fear in such a way that, if he does not win love, he avoids hatred; because he can endure very well being feared whilst he is not hated." According to Hobbes, when men enter into a commonwealth so that they can live peacefully with one another, they are moved partly by reason and partly by their passions. "The passions that incline men to peace," he writes, "are fear of death; desire of such things as are necessary to commodious living; and a hope by their industry to obtain them." But once a commonwealth is formed, the one passion which seems to be the mainspring of all political activity is "a perpetual and restless desire of power after power, that ceaseth only in death"; for a man "cannot assure the power and means to live well, which he has present, without the acquisition of more." Not all political thinkers agree with the answers which Machiavelli and Hobbes give on such matters; nor do all make such questions the pivots of their political theory. But there is general agreement that the passions are a force to be reckoned with in the government of men; that the ruler, whether he is despotic prince or constitutional officeholder, must move men through their emotions as well as by appeals to reason. The two political instruments through which an influence over the emotions is exercised are oratory (now sometimes called "propaganda") and law. Both may work persuasively. Laws, like other discourses, according to Plato, may have preludes or preambles, intended by the legislator "to create good-will in the persons whom he addresses, in order that, by reason of this good-will, they will mote intelligently receive his command." But the law also carries with it the threat of coercive force. The threat of punishment for disobedience addresses itself entirely to fear, whereas the devices of the orator--or even of the legislator in his preamble--are not so restricted. The orator can play upon the whole scale of the emotions to obtain the actions or decisions at which he aims. Finally, there is the problem of whether the statesman should exercise political control over other influences which affect the emotional life of a people, especially the arts and public spectacles. The earliest and perhaps the classic statement of this problem is to be found in Plato's Republic and in his Laws. Considerations relevant to the question he raises, and the implications of diverse solutions of the problem, are discussed in the chapters on ART, LIBERTY, and POETRY.

|

||

|

|