|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

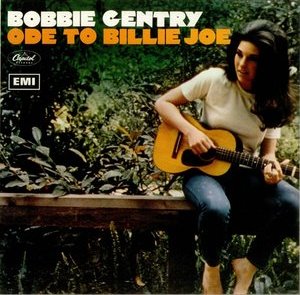

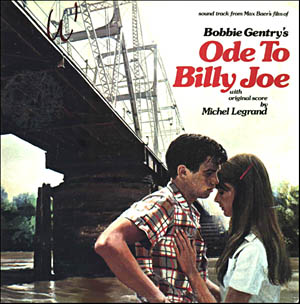

Tallahatchie Girl and Billie Joe

Editor's note: I originally wrote this piece as part of an online "Ode To Billie Joe" discussion, “What did they throw off the bridge?” Later, I decided to add it to the “Perfect Mate” collection of vignettes.

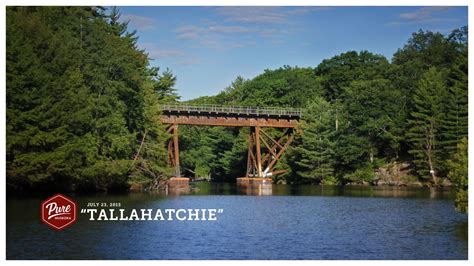

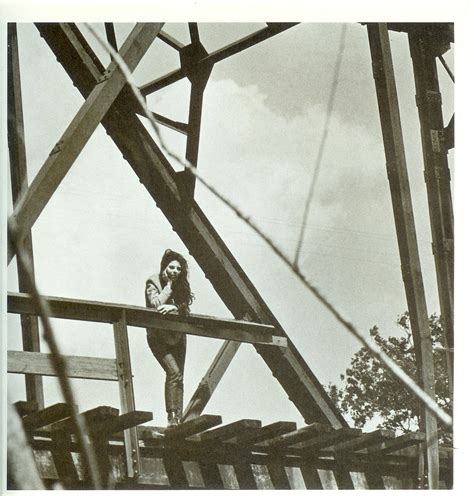

It was the third of June, another sleepy, dusty Delta day I was out choppin' cotton and my brother was balin' hay And at dinner time we stopped and walked back to the house to eat And Mama hollered out the back door "Y'all remember to wipe your feet" And then she said "I got some news this mornin' from Choctaw Ridge" "Today Billie Joe MacAllister jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge" And Papa said to Mama as he passed around the blackeyed peas "Well, Billie Joe never had a lick of sense, pass the biscuits, please" "There's five more acres in the lower forty I've got to plow" And Mama said it was shame about Billie Joe, anyhow Seems like nothin' ever comes to no good up on Choctaw Ridge And now Billie Joe MacAllister's jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge And Brother said he recollected when he and Tom and Billie Joe Put a frog down my back at the Carroll County picture show And wasn't I talkin' to him after church last Sunday night? "I'll have another piece of apple pie, you know it don't seem right" "I saw him at the sawmill yesterday on Choctaw Ridge" "And now you tell me Billie Joe's jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge" And Mama said to me "Child, what's happened to your appetite?" "I've been cookin' all morning and you haven't touched a single bite" "That nice young preacher, Brother Taylor, dropped by today" "Said he'd be pleased to have dinner on Sunday, oh, by the way" "He said he saw a girl that looked a lot like you up on Choctaw Ridge" "And she and Billie Joe was throwing somethin' off the Tallahatchie Bridge" A year has come 'n' gone since we heard the news 'bout Billie Joe And Brother married Becky Thompson, they bought a store in Tupelo There was a virus going 'round, Papa caught it and he died last Spring And now Mama doesn't seem to wanna do much of anything And me, I spend a lot of time pickin' flowers up on Choctaw Ridge And drop them into the muddy water off the Tallahatchie Bridge

I believe the key to deciphering “Ode To Billie Joe” hides within a report of the narrator’s lunch-time appetite. She’d eaten a first piece of apple pie, no problem at all. But a sudden shocking realization, slowly creeping over her, brought on a degree of nausea. This small detail speaks of a certain sense of detachment, which will help us to discern meaning. Let’s step back and survey the entire field. Ms. Gentry flatly asserts that there is no meaning to this song; that, she made it all up. Should we believe her, or does “the lady protesteth too much”? I do not follow the lives of celebrities, but I am told that “Ode To Billie Joe” was for the writer a “one-hit wonder.” We sense this is by design. Ms. Gentry, obviously, is very talented, and, we require little persuasion to believe that she might have produced many songs. But, we infer, she loves her privacy more than the limelight. But why did she emerge from obscurity at all? Did she have a message to proclaim, a mission, which, having fulfilled it, removed herself from the public glare, back to the sanity of her own thoughts and purpose? “Ode To Billie Joe” does not offer us an historical account. Yet, as the phrase goes, while “it is fiction, it really happened.” This song, at least in bits-and-pieces, presents a story of EveryBoy and EveryGirl. That’s why it’s enjoyed mammoth success. People relate to it, and each of us sees him or herself doing the same things, to various degrees, at certain stages of life. I was 16 when this song was new. And I can still see myself riding a John Deere 4020 tractor while listening to this new addition to the “hit parade.” And if there’s a universal, albeit runic, message in “Ode To Billie Joe,” we’re left to make sense of it by carefully weighing the internal evidence, but without committing the literary mortal sin of eisegesis, that of reading into the text what the context will not support. The simplest answers to a question should be entertained first. I cannot accept, the text itself will not support, a deep-and-dark deed such as casting a little fetus into a river. If a young girl had been party to such an act, she would not likely be feeling fine two days later, blithely asking for “another piece of apple pie”; no, not for a long time to come. And if I were to suffer the misfortune of feeling the need to dispose of a tiny body, I certainly wouldn’t do this in broad daylight, under the judging eyes of neighbors and preachers. “Ode To Billie Joe,” all things considered, is about two lovers terribly “out of phase” with each other. This is the norm with romantic love: He’s ready, but she’s not; then she’s willing, but he’s gone. It’s the norm because people develop at different rates, and it’s really hard to choreograph this synchronized dancing. Billie Joe had liked her for a long time, even from the early years; that’s what the frog down her back was all about. He was trying, so very unskillfully, to get her attention. I still wince to recall my own versions of this dynamic at a young age. As many have pointed out, Billie was from the “wrong side of the” bridge. This fact caused her to be less than totally forthcoming at the lunch-table, but we detect no “better than thou” attitude from her. She just doesn’t feel the same as he does. Not yet. Mother isn’t necessarily trying to “marry her off.” The reference to Brother Taylor as the “nice” young man is quite typical from older women of religious persuasion. I’ve heard older women use these very same words for the new preacher in town. And the view that Brother Taylor fought Billie to the death is just bunk. The preacher’s presence in this song is part of the ambiance, the backdrop cultural setting, as are the mentionings of black-eyed peas, a sawmill, or Becky Thompson. There is no hidden cosmic significance in any of these mundane, arbitrary references. We should comment, though, that Brother Taylor, near the bridge, was close enough to make out the features of Billie, but he would later deny being able to recognize the narrator. And if his statement means anything we might interpret this as a certain religious haughtiness: “Nice girls don’t go the Choctaw Ridge area, and I’ll cover for you this time, but I want you to know that I know.” That second piece of apple pie came laced with the beginnings of mental discord – “you know, it don't seem right." She’s genuinely puzzled; at least, for a moment. She authentically wonders about the sawmill incident, and sees no reason to hide the fact of this meeting. Inwardly, she is thinking, “He acted ok. I thought we were good, that everything was fine, that he’d moved on.” But then, outwardly, primarily answering herself, she exclaims to the table, “and now you tell me” he’s done something rash. She had met him, very recently -- before the sawmill incident, it seems – on the bridge. Why on the bridge? He doesn’t feel socially at home and generally accepted on her side of the bridge, so she offers the concession of meeting him half-way. She’s a polite and sensitive girl, not wishing to hurt a boy who has feelings for her, but she needs this meeting, too. She wants to close it off between them and not leave him with false expectations. She’d tried to do this after church that night, but he was still hopeful. This time, however, she would have to speak more plainly, so as not to be misunderstood.

He’d given her something, some token of affection. She could not accept it. Was it a ring? I think not. This would not be large enough for a passerby to notice in its fall. It may have been his love-letter. She could not accept his wild words. She had to stop this now before it escalated. She returned the letter to him, on the bridge, and they mutually, and amicably, decided to tear up the letter, and throw it into the river below. The preacher walking by saw the fluttering pieces. I say “amicably” because, she thought, "wasn’t he cool with it all when we met at the sawmill?” But smiles have hidden many a broken heart; and searing feelings of rejection, at their worst, might incite to madness. I’m reminded of one of the earlier love-letters between Elizabeth Barrett and Robert Browning. He’d come on too strong, too soon, and Elizabeth lashed out at him, demanding, having returned the letter, that he destroy it and never speak, or even think, of such things again. Well, calm down, Elizabeth; she and Robert were married but a year later. Editor's note: Elizabeth, the great artist, could be a hot-head if she wanted to. Her sometimes fiery and flamboyant nature might send her to hyperbole. Under her breath, however, we hear the whispering mitigation: "Just because I say no today doesn't mean it's no forever." And in my own youth, I recall an incident, one best left undefined, in which I had given a letter and a gift to a certain girl, but she reacted not like the polite narrator and much more like the rabid Elizabeth. I can speak with Billie Joe to tell you that this kind of dramatic repudiation really stings; “sting” doesn’t cover it. Billie at the sawmill might have acted like he’d moved on, but his wounds were still flowing with real red blood. Only seconds after asking for that second piece of apple pie she began to put two-and-two together. He was not ok, after all. His nonchalant smile and studied joviality at the sawmill were just false bravado: "And now you tell me Billie Joe's jumped off the Tallahatchie Bridge." It is often true in life that we don’t know what we have until we lose it. It’s part of a universal process of coming to awareness, it seems. Did the narrator later realize that she loved Billie after all? I think we may reasonably surmise this. She had done nothing wrong by returning his gift and speaking plainly to him. She needed to do this. And in light of her reasonable conduct, she would harbor no substantial feelings of guilt over what Billie did. No proximate cause could be drawn from his actions to hers. She would feel bad about the whole thing, of course – any sensitive person would. But, without a romantic interest, she would soon put it all behind her; and with a clear conscience. But she, in fact, cannot let this go. In his absence, that “out of phase” element begins to take its vengeance, and now, with roles reversed, she is the one hopelessly soliciting him… by throwing flowers, a belated gift of love, off the old bridge.

It is not unknown in history for writers to speak obliquely, cloaking a primary message. We write, are sometimes compelled to write, about that which we know. Ms. Gentry told us the truth when she said that the story of Billie Joe never happened… But, some of the story’s aspects did happen to her, as they’ve happened to each of us. That’s why we can’t forget this song, and that's why she wrote it.

Kairissi. The great psychologists instruct us that to become aware of one’s truest desires requires a great deal of maturity. Elenchus. And that’s a Tallahatchie Bridge too far for almost all of us. K. Yes. When we’re “young and stupid,” what we believe to be authentic desire is just the Ego’s needing and wanting. The deeper soul-longings usually have no part in it. E. Class is in session, though. Later, we sometimes learn that, what we thought we didn’t want, is exactly what we wanted – a revelation descending upon us only when it’s gone; when it's too late. K. The story of Tallahatchie Girl and Billie Joe, with its deep-South rural setting, on the mundane level, might find resonance with only a few. However, this story has enjoyed wide interest and appeal. E. And we know why. It’s not just about two kids in a southern farming community. There are aspects of this narrative which represent universal “coming of age” rites of passage. K. And in that larger sense, it’s a story about all of us. And, as usual, we find two proto-lovers terribly out-of-phase with each other. E. Are there other kinds of lovers? K. Only in the fairy-tales, I think. E. As we’ve established in other discussions, all love stories are the same in certain respects, but each one is also unique. What is different about this story, among the many we’ve reviewed? K. One thing – they come from opposite sides of “the tracks,” or, in this case, the bridge. Caste systems are in vogue not only in India. In every community, people know the boundaries of the “good” neighborhoods and the “bad.” E. “Nothing ever came to any good up on Chaktow Ridge.” K. That’s right. And, without a doubt, this factor played at least some small part in an immature girl’s antipathy toward Billie Joe. E. Nice girls don’t date “boys like that” from the wrong side of the bridge. K. (sighing) E. I’d like to say something on behalf of my species. We like to play “macho” and act tough, but it’s a very closely held secret that, I would say, boys are far more psychologically vulnerable than girls regarding being rejected socially. The sting of being rejected by a valued girl is more than a sting – it’s a poison dart. And a lot of boys, though they’d really like to be with a girl, oftentimes will remain reclusive, and will stand alone, rather than risk being told “no” by an object of desire. K. I think girls may have some idea of this, but, I suspect, not to the degree of which you speak. I suppose we’re taken in by the “macho” propaganda and find it hard to believe that rejection could be all that devastating. E. Some might say that Billie Joe’s reaction, jumping off the bridge, is an extreme case; and maybe it is. But, then again, while many boys might not go that far, a rejection by a sought-for girl can easily scar him for life. K. (silence) E. In my travels, I’ve noticed that there are some girls, a great many actually, who are very cruel in this regard. They count it a big joke to fend off the invitations of, shall we say, less glamorous boys, not realizing, or not caring about, the near-permanent damage inflicted upon the soliciting boy. It is the most rare girl who, unwilling to cause damage, will tenderly, with graciousness, turn aside an unwanted request for social concourse. She is a real gem, and a highly-spiritually minded creature. K. (silence)

|

||

|

|