|

home | what's new | other sites | contact | about |

||||

|

Word Gems exploring self-realization, sacred personhood, and full humanity

Philanthropy, Charity, Service Schopenhauer

Schopenhauer and the hero, risking one's life for another at the sudden realization of oneness with all

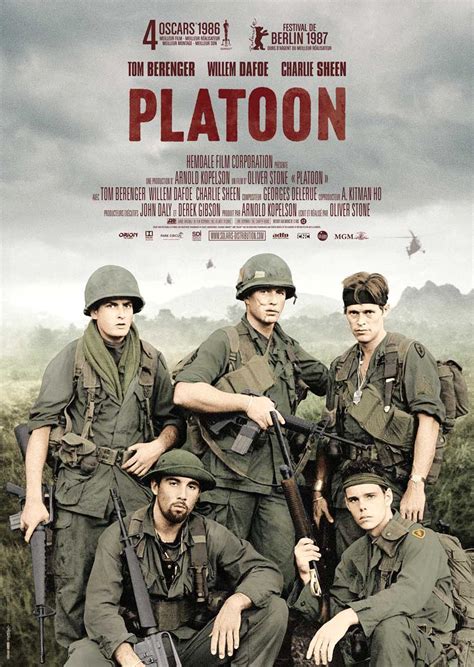

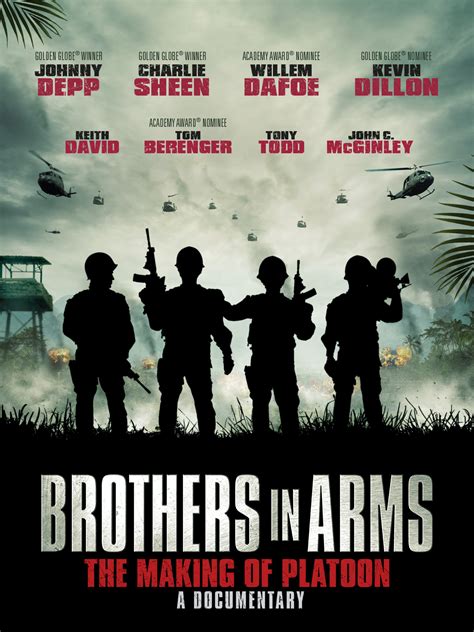

E. It's commonly stated, and with the gravest authenticity, that fighting men during war forge a strong bond among themselves, the strength of which is unknown to the rest of society. K. It’s somewhat strange, isn’t it. The average person in society, well fed, with a roof against the rain, often will act in a selfish manner toward fellow human being. But soldiers, facing privation and death each day, will create bonds of brotherhood, exemplifying the greatest acts of heroic service. E. I was watching the 1986 movie Platoon about Vietnam. K. Did you like it? E. It’s really not a movie you watch for entertainment. It revealed the horrors and atrocities of that war. Vietnam vets have said that the portrayal was extremely and brutally accurate. And then I watched a documentary on the making of the movie. It was really something. I don’t think this had ever been done before. The actors didn’t really know what they were getting themselves into. K. What do you mean, Elenchus. E. The film was shot in the hinterland jungles of the Philippines. For three months they were cut off from the main cities and towns. Two or three of the young actors were somewhat well known in Hollywood but the couple dozen or so of the others were “unknowns,” had never been in a movie. They thought it would be a 9-5 job with American-style living accommodations during off hours. But director Oliver Stone, a real Vietnam vet, had a different idea. He wanted raw realism and no Polyanna faces. He wanted his guys not be actors but to feel the real heat and trauma of trying to stay alive in dystopian conditions of war. K. This is rather more than driving to a movie set each morning in your sports car. E. Stone hired a real Marine commander (retired) to whip these guys into shape. And we’re not talking about just aerobic exercises, but to live as real soldiers: no showers, no clean clothes, no good food, sparse clean water for stretches of time; no phone calls, stinging red jungle ants crawling down your back, slithering cobras in the brush, trudging miles in 110 degree heat. As the weeks of film shooting wore on, the men no longer saw themselves as actors but as actual soldiers, learning to survive in forbidding conditions. You’ll want to see the documentary for the full report. K. This is incredible. E. But here’s why I’m bringing all this to our attention. And it has to do with “Schopenhauer’s hero.” When these guys got back to the States, they were not the same. K. They had been through an ordeal. E. It felt like returning from a real war. And those who went through this gauntlet of pain, to restate, did not see themselves as actors. Now they were brothers, called themselves brothers, and, if they could, met regularly, like family. Decades later, they were still close and stayed in touch. All of them said they’d never gone through anything like it. It changed them. K. Elenchus, say more about the “Schopenhauer hero” factor. E. It’s too bad, isn’t it. Why do we have to go through the horrors of war, or even a very convincing simulated one, in order to experience the brotherhood of man? K. (silence) E. It’s very sad, very dismaying, that so many of us treat each other so shabbily, so selfishly. And why do we do this? Are we not all brothers and sisters? Why do we live in a dark cloud of illusion, unaware that we all share a connection? K. Schopenhauer seemed to be saying that, in times of great duress, the common barriers that divide people suddenly break down. Now the ego’s lie that we’re all separate is exposed. All of a sudden we naturally find ourselves willing to lay down one’s life to help another. We’re all brothers and sisters after all.

|

||||

|

|